When Bernard Baruch purchased Hobcaw Barony in 1905, most African Americans living on the property were illiterate. This was the shameful legacy of a 1740 South Carolina law making it illegal to teach slaves to read.

The law was flouted during the Civil War, when Union forces occupied St. Helena Island in the Lowcountry and set up the Port Royal Experiment, the first large-scale government program to help freed slaves.

In the photograph below, Laura Towne, a Port Royal volunteer from Pennsylvania, instructs freed children in an open-air classroom.

In 1868 the state’s Reconstruction legislature wrote a new constitution guaranteeing free public education for all children, black and white. But equitable funding for public schools in South Carolina was not fully established.

As the state’s former Confederate leaders regained power, unequal support for the education of African Americans became official state policy. All along, many black families relied on private schools, some with church affiliations.

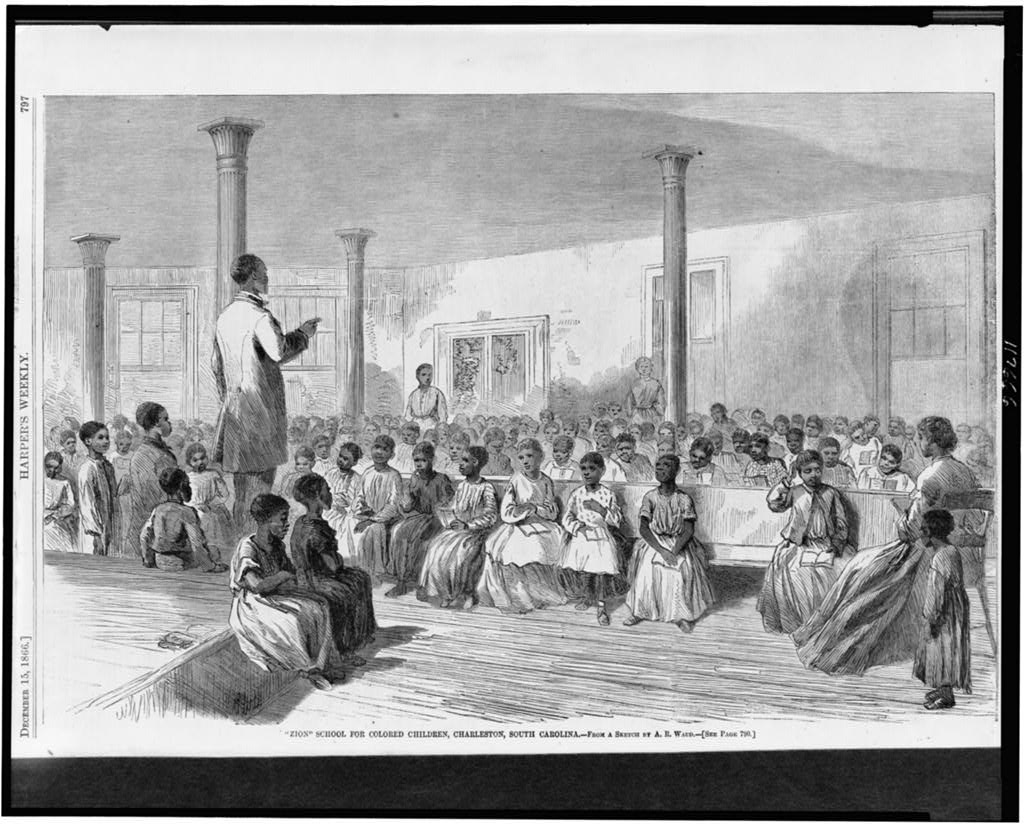

In this engraving from Harper's Weekly, African-American children attend the Zion School for Colored Children in Charleston, SC, in 1866.

In his memoir, Bernard Baruch writes that, at his mother’s urging, he “always sought to improve conditions [in the South] and somehow to help improve the Negro’s lot.”

In 1915 Baruch constructed a private school at Strawberry Village for the black children of Hobcaw Barony, part of what he called “a general plan to rehabilitate the plantation.” The one-room Strawberry School had one teacher for children in first through fifth grade.

The closest schools for blacks and whites were in Georgetown, and while children of the estate’s white residents boarded a daily ferry to go to school, no such transportation was afforded to its black community.

In 1935, Baruch upgraded the buildings in Hobcaw's African-American villages. He enlarged Strawberry School to the size that it is today.

Minnie Kennedy and her siblings went to Strawberry School, which provided a basic elementary education. Daisy Kennedy, like many adults on Hobcaw, learned to read as an adult, taught by her children.

After they graduated from Strawberry School, the Kennedy children went to Howard School in Georgetown and stayed with their grandmother in a house purchased by William and Daisy Kennedy, who continued to work for the Baruchs.

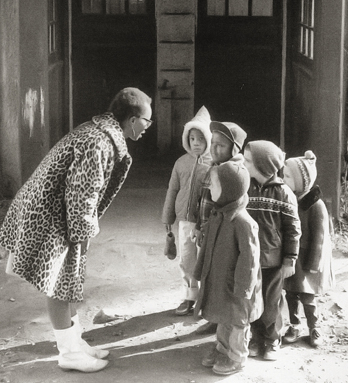

Minnie Kennedy was passionate about education from an early age. She graduated from South Carolina State University and pursued a teaching career in Greenburgh, New York, where she became principal of a Head Start program.

In this photograph she is talking with pre-school students at her school.

In 1966 Ms. Kennedy was asked to join the faculty of the New York University School of Education. She also taught at Connecticut State College, the Adelphi University Urban Education Center, and The City College of New York Comprehensive Day Care Teacher Training Center.

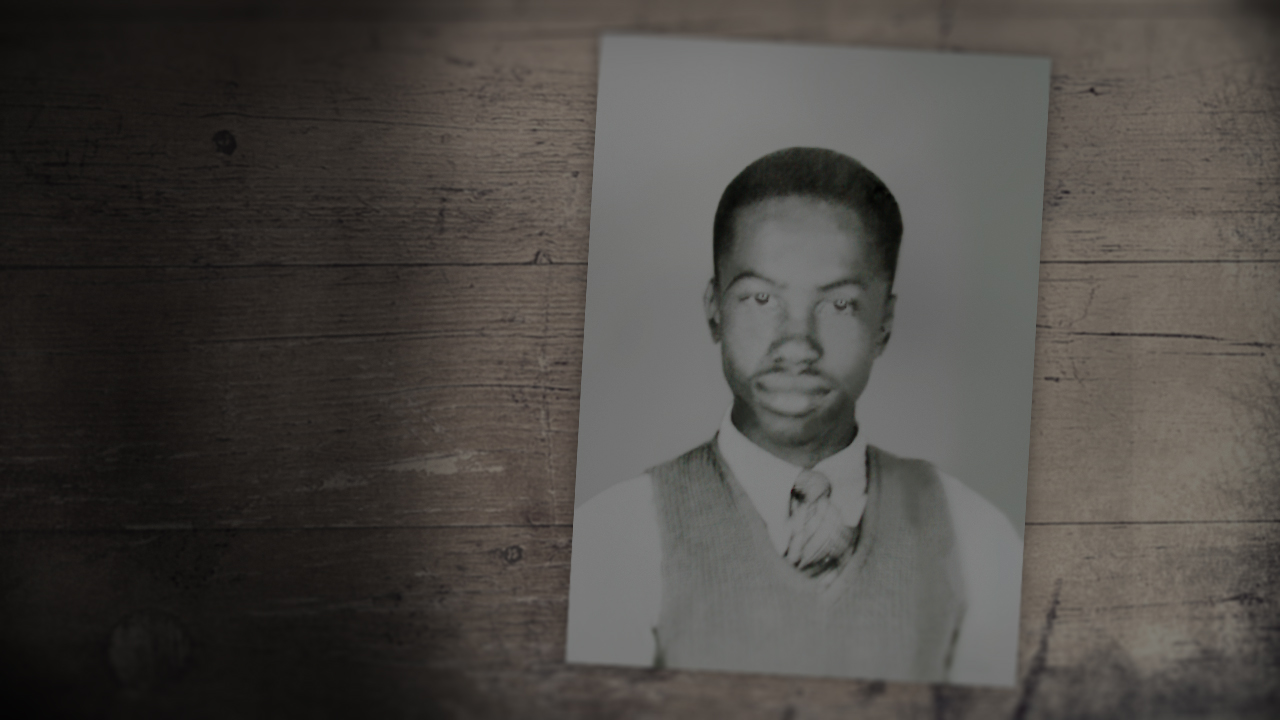

Robert McClary’s family moved to Friendfield Village in 1930 when Robert was seven years old.

Robert craved an education and attended Strawberry School, but his attendance was erratic because he and his sister Myrtle had to go to school on alternate days.

In his autobiography, Sandy Island, Cedar Swamp, Hobcaw and Beyond. My Story - My Life, Robert McClary describes in painful detail the life of a poor, black child on Hobcaw Barony in the 1930s.

Being responsible for my younger brothers and sisters at such a young age has had a profound effect on my life. Because of my having to look after, cook for, feed and protect them, I could never play or engage in any games or competitive sports. There was no time. Of course there were no organized games of any kind at Hobcaw. Besides, I was also working for Mr. Boykin and taking care of the plantation's chickens and hunting dogs. On days that I was to babysit, I had to get up very early to walk two miles to Mr. Boykin's house, passing my school on the way. I fired up the kitchen stove for the cooking of breakfast. I fed and watered the chickens and dogs down at the doghouse. Then I returned home, again passing the school on the way. Myrtle would then go to school, because it was her day to attend.

Sandy Island, Cedar Swamp, Hobcaw and Beyond. My Story - My Life

Joshua Shubrick attended Strawberry School in the 1940s. He and his mother lived in Georgetown, and Joshua rode to school with the teacher, Ms. Jackson.

On a visit to the school with the ETV crew in 2015, Mr. Shubrick remembered that there was a blackboard, but few books, and that his favorite subject was math.

The only bathroom for the students and teacher was an outhouse, as there was no running water, and no electricity, in Strawberry School.

To return to the trail click NEXT STOP

To return to the Strawberry Schoolhouse click