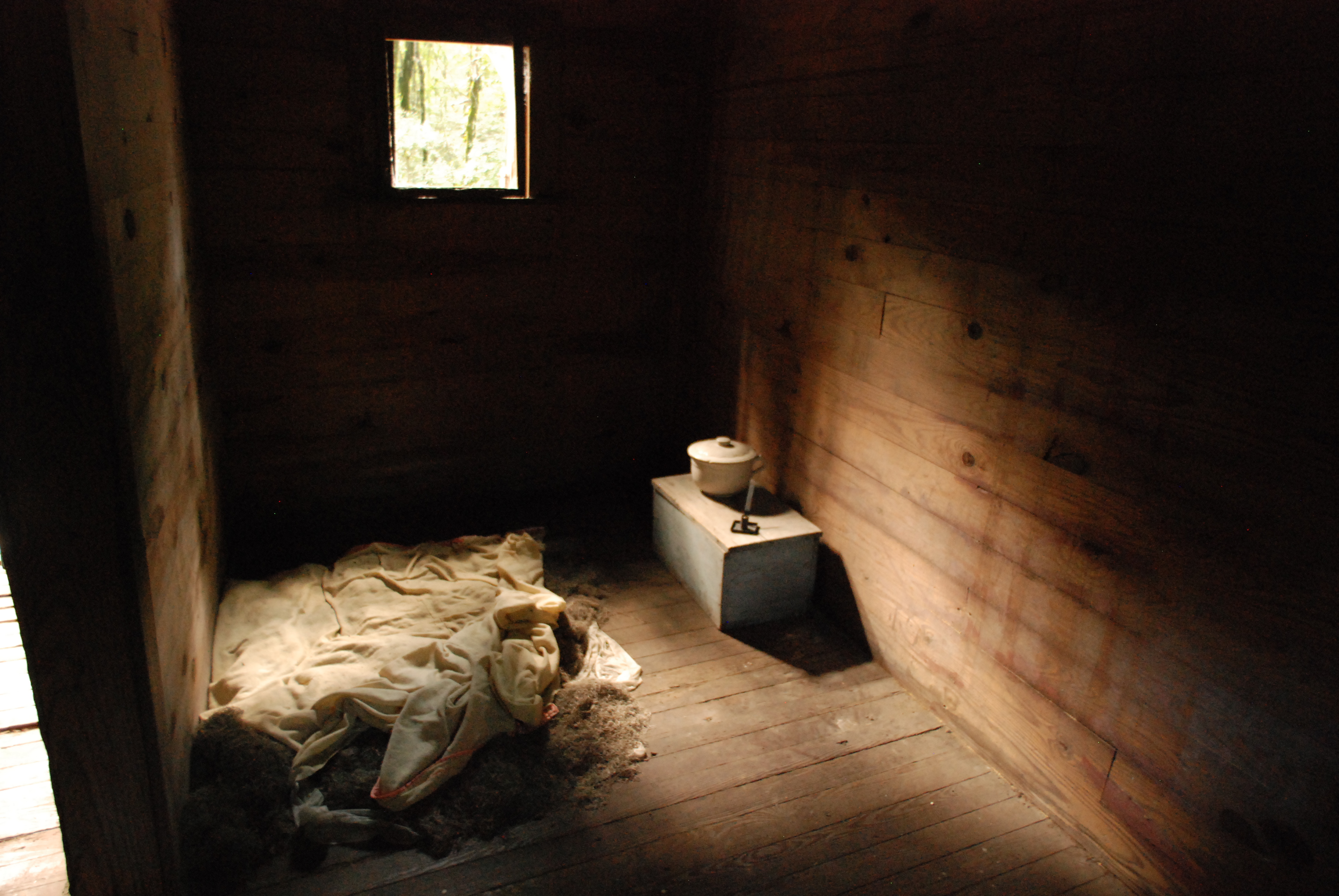

While the Carr dwelling is small, evidence suggests its floor plan was familiar to West Africans, whose homes averaged only ten-by-ten feet. This doorway leads to the only bedroom in the cabin, though the enslaved people living here would have had to use all of this small space, including the main room and attic loft, for sleeping. A bedroom offered a minimal degree of privacy.

Here, there is no actual bed; instead, a sheet and Spanish moss serve as mattress and insulation. Native Americans called Spanish moss “tree hair” but French colonists changed its name to “Barbe espagnole,” or “Spanish Beard,” to ridicule their Spanish rivals. All utilized it as a natural resource. The chamber pot is a reminder that none of the dwellings in Hobcaw's African-American villages had indoor plumbing, though they did have outhouses.

Like all the structures in Friendfield Village, the Carr home had no electricity. When the shutters were closed the dark interior was lit solely by the fireplace and candles. In the 1930s Bernard Baruch began to add glass windows to some of the houses in Friendfield Village as an incentive to residents to remain on Hobcaw Barony, but Laura Carr resisted changes to her home. On March 20, 2015, Joseph McGill of the Slave Dwelling Project spent the night in Laura Carr's house, where he was interviewed by the ETV crew. Here he reflects on the fact that none of the homes in Friendfield Village ever had electricity.

In addition to the fireplace, candles were the most convenient and resourceful way to light plantation dwellings, and making the candles was a job that often fell to enslaved African Americans. Using tallow rendered from leftover beef fat, or lard rendered from hog fat, they repeatedly dipped cotton wicks into the waxy substance - dipping, drying, and dipping again - until candles were formed.

In the 1930s, the federal government’s Works Progress Administration undertook an ambitious project to interview a vanishing generation of people who had been enslaved. The narrative of Yach Stringfellow, a 90-year-old former slave of a Texas plantation, includes an anecdote on candlemaking, as transcribed by the interviewer c. 1936 - 38:

Dey worked a long time gittin ready fer de candle dippin'. Dey mos en allus dipped de candles in de fall ob de year. De womin folks saved all de tallow from de beefs an sech. Ef a cow got herself killed dey allus tried to save de tallow case it took a lot of candles to light up ole Marster's big house.