The idea for victory gardens originated during World War l, as a way for ordinary citizens to support the war effort by producing their own food. The government, which rationed essential foodstuffs such as sugar, dairy products, eggs and coffee, encouraged people to grow their own fruits and vegetables to reduce pressure on the public food supply and maintain a healthy diet. Homegrown food also required less transportation, so that more fuel could go toward the war.

Originally called war gardens, the victory gardens were planted on available public and private land, including backyards, parks, empty lots and rooftops, involving city dwellers as well as those living in the country. The victory garden movement was revived during World War ll, and Belle Baruch planted a large plot on her Bellefield Plantation property. With a stable full of horses, she had a steady supply of fertilizer. In this clip from the Baruch home movies, Belle and her assistant Lois Massey harvest vegetables.

The Eastern Oyster is abundant in the tidal creeks that wind through the marshes of Hobcaw Barony and has long provided sustenance for the residents of the Waccamaw Neck. Oysters were a favorite food of native people, as confirmed by numerous shell middens - ancient deposits of oyster and clam shells along the shore. South Carolina oysters are of the intertidal variety, meaning that they grow in the area exposed between high and low tides, and are generally in season during months with an “R” - namely, from September through April.

The Baruchs frequently served oysters to their guests, whether at outdoor oyster roasts or in the dining room; longtime assistant Lois Massey recalled fixing oysters on the half-shell for a formal dinner of twenty-four people. In the 1940s Belle Baruch and Nolan Taylor, the Hobcaw plantation supervisor, took over management of the Hobcaw oyster beds. In this photograph from around 1970, Taylor and his son, Bernie (named for Bernard Baruch) are gathering oysters using two boats tied together.

The architecture of Hobcaw House makes a clear distinction between the areas for family and guests and those for servants, but unlike an “upstairs/downstairs” design, it divides these worlds between the front and back of the house. The servants’ entrance in the rear opens into the service wing that includes a porch, kitchen, butler’s pantry, servants’ dining room, several storage rooms and a staircase leading to two floors of sleeping quarters with seven bedrooms.

While African-American servants worked in the service wing, they did not sleep there or even use the bathrooms, and black children who lived on the plantation had to go downstairs to the basement area to wait for their parents. In this photograph of the rear of Hobcaw House, taken in 1972, the service wing is clearly visible on the left.

Much of the food eaten by the Baruchs, visitors to Hobcaw Barony, and resident African Americans was grown, caught or gathered on the land and in the waters surrounding the property. In the early days of the twentieth century, wildlife was abundant, especially the migratory waterfowl that wintered in the former rice fields.

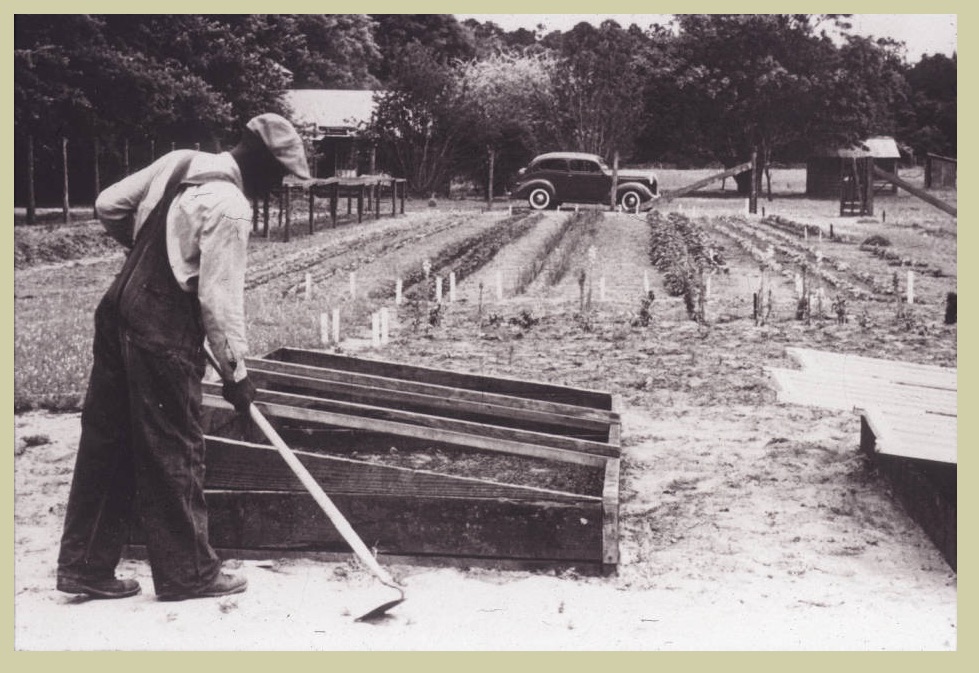

Everyone on the plantation, black and white, hunted and ate wild game, including deer, ducks, turkey, quail and many varieties of fish and shellfish. The Baruchs did not cultivate rice, the traditional crop, but vegetables, including potatoes, beans and collards were grown on Hobcaw, cultivated by African Americans living on the property, such as Joshua Jenkins, pictured here. Delicacies, including fine wines and liquor, had to be purchased elsewhere.

In the kitchen of Hobcaw House, where elaborate meals were prepared for the Baruchs and their guests, black and white chefs worked together. The Baruch family brought a cook with them from New York, and they hired cooks who lived in Hobcaw's African-American communities, including Maudess McClary, Daisy Kennedy and Charlie McCants. In this c. 1916 photograph Hobcaw chef Charlie McCants stands on the steps of the Clambank Landing hunt cabin with a young Belle Baruch and guests.

It is interesting to imagine the creolization of foodways that took place here, as the kitchen staff blended European cooking practices and ingredients with Lowcountry customs and local fare.

Food historian Michael Twitty discusses the delicious consequences of the fusion of European and African food traditions.