Following the Revolutionary War, South Carolina's Jewish population surged. Charleston had one of the largest Jewish populations in the country and offered economic opportunities and a degree of religious tolerance remarkable for the time.

By 1800, Charleston was home to the largest, wealthiest, and most cultured Jewish community in North America – upwards of five hundred individuals, or one-fifth of all Jews in the nation.

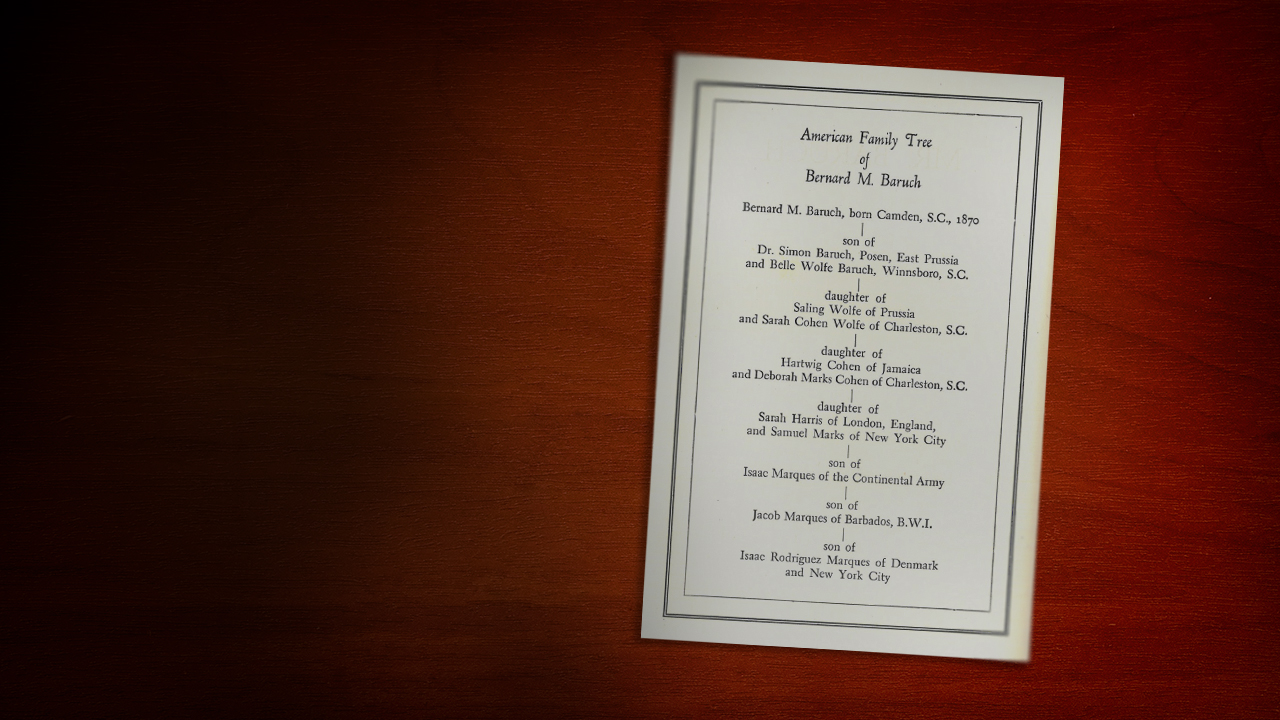

On his mother’s side, Bernard Baruch came from a very old Jewish-American family.

Sarah Cohen Wolfe, Bernard Baruch’s maternal grandmother, pictured on the left in this 1910 photograph, traced her ancestors to Sephardic Jews who immigrated to New York in the 1690s, and in the 1700s moved to Charleston, South Carolina.

In his memoir, Bernard Baruch writes:

The first of Mother's ancestors to reach these shores was Isaac Rodriguez Marques, whose name is also spelled in old documents as Marquiz, Marquis, and Marquise. Arriving in New York sometime before 1700, he established himself as a shipowner whose vessels did business with three continents.

My Own Story

Isaac Marks, grandson of Isaac Rodriguez Marques, was born in 1732 and served in the Continental Army. His son, Samuel, who was born in New York City, moved to Charleston, South Carolina as an adult, establishing the family's connection to the Palmetto State.

Samuel married Sarah Harris of London, England, and their daughter, Deborah, married Hartwig Cohen, rabbi of Charleston's Sephardic Beth Elohim congregation.

Their daughter, Sarah, married Saling Wolfe, a wealthy Jewish planter and slaveholder from Winnsboro, South Carolina in 1845. The Wolfes lost their land and fortune during the Civil War

Sarah and Saling Wolfe had 13 children. In 1867 their daughter, Isabelle, married Simon Baruch, a country doctor and Confederate veteran, who had emigrated from Prussia at the age of 15.

Isabelle and Simon Baruch embodied two sides of the American Jewish experience – that of the new immigrant and the old, pre-Revolutionary family.

They had four sons - Hartwig, Sailing, Herman and Bernard, pictured here from left to right, with Annie Griffen Baruch on the end.

Bernard and Annie Baruch raised their children as Episcopalian, yet the Chapin School, which Annie had attended, refused to admit her daughters because of their Jewish heritage.

Despite his desire to serve the public good, Baruch never ran for office or accepted a cabinet post.

After World War I he was considered for Secretary of the Treasury and possibly Secretary of Commerce, but, according to at least one of his biographers, he declined for two reasons – his fortune, which he had gained as a speculator, and his Jewish birth.

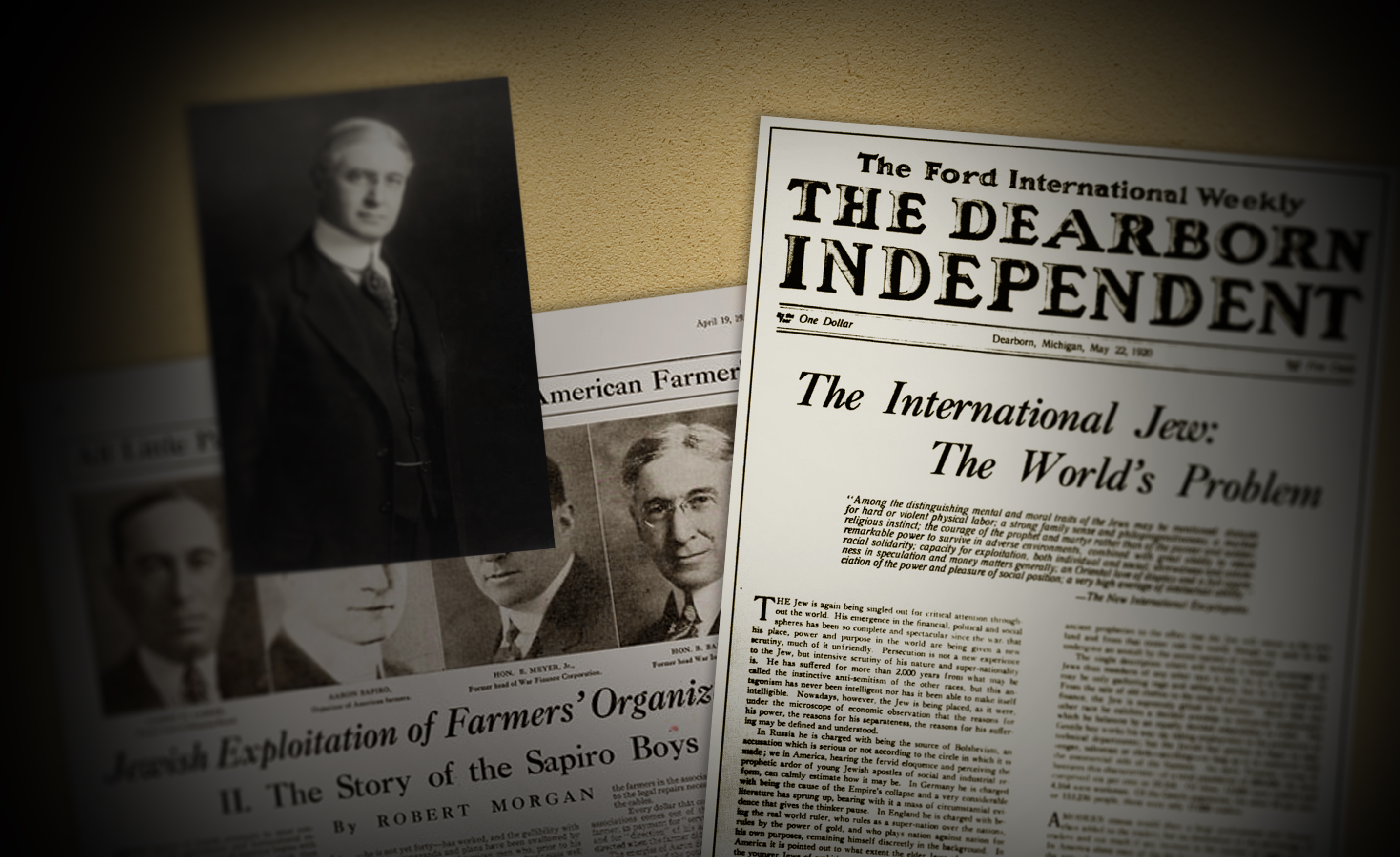

Certainly there was no lack of anti-Semitism. The car manufacturer Henry Ford, an acknowledged anti-Semite, accused Baruch of being part of a Jewish conspiracy to control the world’s economy.

Whether or not Bernard Baruch actually believed that his being Jewish made him a political liability – as he apparently said on more than one occasion – he officially attributed his reluctance to hold office to a desire for autonomy:

“I myself have always felt that I could contribute more as an independent private citizen than as a public officeholder. By maintaining my independence, free of the obligations which so often accompany office-seeking, I felt I could best fulfill my conception of public office.”

Bernard M. Baruch, The Public Years

To return to the trail click NEXT STOP

To return to the Hobcaw House Living Room click