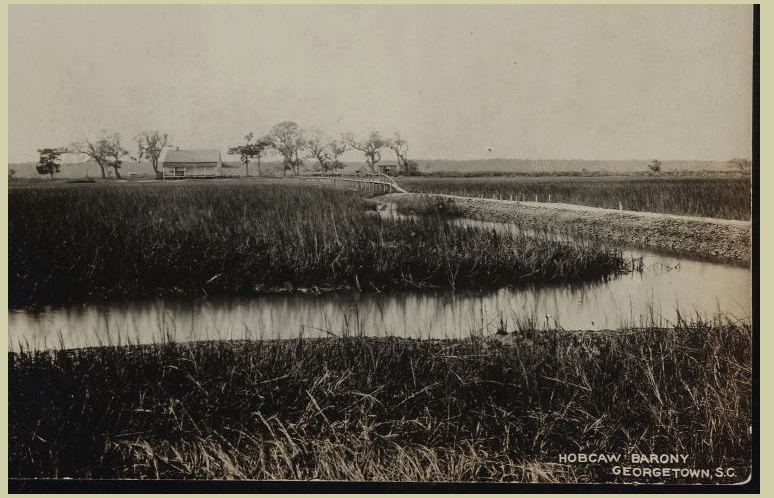

Clambank Landing is located on Town Creek in the North Inlet estuary. Far enough from the ocean to be somewhat protected, it has been popular with visitors to the area for untold numbers of years. Ancient shell middens at Clambank indicate Native Americans frequented the spot over many centuries. This series of photographs tells different aspects of the Clambank Landing story. In the first shot, from 1905, the former summer home of a rice planter, dating to the 1840s, and its outbuildings are the only structures. A man-made shell causeway leads to the water.

In this photo, from 1910, a footbridge has been built over the causeway and a new building, Baruch’s hunt cabin, sits next to the old summer house. In the foreground of the picture is a bateau filled with duck decoys made by the Caines brothers for Bernard Baruch.

This picture, also from 1910, shows George Shubrick, a resident of Hobcaw Barony and a skilled hunting guide, holding a duck from a morning’s shoot.

In this photograph, from 1937-38, Belle Baruch and Lois Massey prepare to cook crabs at the dock at Clambank Landing. The daughter of Samuel T. Massey, Hobcaw's superintendent of plumbing and electricity, Lois was Belle's secretary and house manager at Bellefield for many years.

The Native American presence at Hobcaw Barony is apparent in the property’s very name, said to be a Native American word meaning “between the waters.” Physical evidence is readily seen in the shell middens that line the shores of Hobcaw’s creeks and emerge as outcroppings in the marshes. Many other material remains have been found at Hobcaw in the form of pottery sherds, blades, points, and numerous other artifacts, yet much archaeological work remains to be done here. In this video,

Buster Hatcher, Chief of the Waccamaw Indian People, who are based in nearby Aynor, South Carolina, discusses the history and present-day circumstances of the Waccamaw and other Indian tribes in the region.

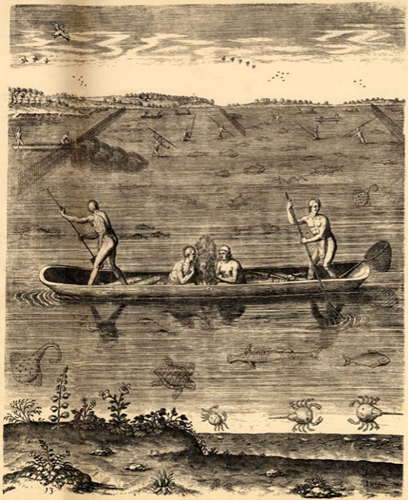

The Manner of Their Fishing, John White, c. 1585. Courtesy the British Museum

Native Americans relied on bodies of fresh and saltwater for food production; they fished and ate a number of aquatic species, such as blue crabs, drum, snapper, flounder, stingray, gar, sturgeon, catfish, and several species of turtle including the diamondback terrapin.

John Lawson, an 18th century explorer and historian, described Native American methods of fishing during his travels from Charleston, South Carolina to North Carolina [spelling and language as quoted]:

They are not only good Hunters of the wild Beasts and Game of the Forest, but very expert in taking the Fish of the Rivers and Waters near which they inhabit, and are acquainted withal. Thus they that live a great way up the Rivers practice Striking Sturgeon and Rockfish, or Bass, when they come up the Rivers to spawn; besides the vast Shoals of Sturgeon which they kill and take with Snares, as we do Pike in Europe. The Herrings, in March and April, run a great way up the Rivers and fresh Streams to spawn, where the Savages make great Wares with Hedges that hinder their Passage only in the Middle, where an artificial Pound is make to take them in, so that they cannot return.

This Method is in use all over Fresh Streams, to catch Trout and the other Species of Fish which those Parts afford… Those Indians that frequent the Salt-Waters, take abundance of Fish, some very large and of several sorts, which to perserve, they first barbakue, then pull the Fish to pieces, so dry it in the Sun, whereby it keeps for Transportation; as for Scate, Oysters, Cockles, and several sorts of Shell-fish, they open and dry them upon Hurdles, having a constant Fire under them. The Hurdles are made of Reeds of Cane in the shape of a Gridiron. Thus they dry several Bushels of these Fish and keep them for their Necessities.

John Lawson, A New Voyage to Carolina, 1709

Migration flyways are corridors that birds travel annually between breeding and wintering areas, heading south in the fall, seeking more food and better weather, and flying back north in the spring to breed. North America is divided into four of these ancient pathways - the Atlantic, Mississippi, Central, and Pacific Flyways.

Hobcaw Barony lies along the Atlantic Flyway, which is the most densely populated of the four. It occupies only 10 per-cent of the U.S. landmass, but it has one-third of the nation’s population. Today, forty percent of the Atlantic Flyway’s bird species are of concern to conservationists.

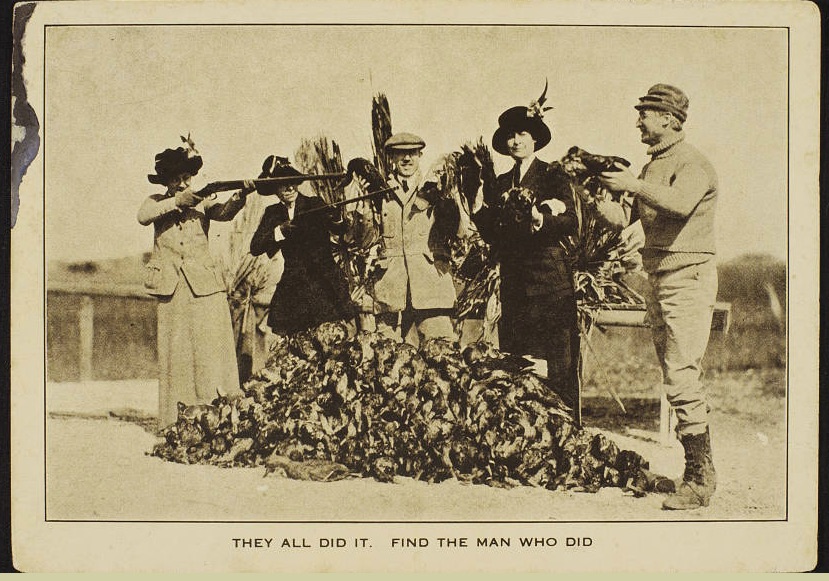

During the early years of the twentieth century, when the Baruchs and their guests hunted ducks at Hobcaw Barony, they often shot more than 100 in a morning, yet hunting is a minor factor in the reduced numbers of birds along the Atlantic Flyway. Habitat loss is by far the greatest threat to migrating waterfowl, making protected areas like Hobcaw Barony increasingly important.

In his memoir, Baruch describes the sight at the beginning of a morning’s hunting expedition:

To the eastward, as the sun rose, one could see tens of thousands of ducks. At times they appeared like bees pouring out of a huge bottle. Their numbers were so great that you had to blink your eyes to be sure you were not suffering from some illusion. As the sun mounted over the horizon, flock after flock would break away from the swamps and rice fields and come down to the marshes, flying in a V-formation.

Bernard M. Baruch, My Own Story