Hobcaw Barony’s landscape includes thousands of acres of salt marsh – transitional areas between land and water that occur along the intertidal shore of estuaries. The North Inlet estuary fills Hobcaw’s marshes twice daily with clean salty water from the Atlantic, providing essential habitat for young fish and shellfish. Crab, oysters, fish and shrimp are plentiful in the marsh creeks, as they were thousands of years ago when Native Americans feasted on them.

The Belle W. Baruch Foundation’s property lines extend to the low tide mark based on a proprietary grant dating to 1718. In this clip from the Baruch home movies, Belle Baruch and friends picnic at her cabana, the Grass Shack, located on the beach near North Inlet.

Belle Baruch founded the Belle W. Baruch Foundation to make Hobcaw Barony available to researchers from all colleges and universities in South Carolina. Since her death two research institutes have been established: Clemson University’s Belle W. Baruch Institute of Coastal Ecology and Forest Science, and the University of South Carolina’s Belle W. Baruch Institute for Marine and Coastal Sciences.

Created in 1969, the Marine Institute was headed from its inception until 1995 by Dr. John Vernberg. In this video Dr. Vernberg describes his first visit to Hobcaw Barony, when he and his wife toured the property with Belle Baruch’s partner Ella Severin. Severin lived at Hobcaw with Belle from 1951 until Belle’s death in 1964. In Belle’s will she was named a trustee of the Foundation and granted lifetime residency at Bellefield Plantation, the home Belle built at Hobcaw. Severin died in 2000 at the age of 95.

The most pronounced archaeological evidence of Native American coastal food production on Hobcaw Barony exists today in the form of shell middens. Consisting mainly of piles of discarded oyster and/or clam shells, middens also contain remains of other foods and artifacts of daily life, such as bone and antler fragments. They can be found next to saltwater creeks, along beaches and on sandbars, and they inform archaeologists, anthropologists, and historians about Native American settlement and migration patterns as well as foodways.

Historical accounts of these middens emphasize the great numbers of shellfish that were eaten. Historian Gene Waddell quotes two early explorers of the colonial Carolinas [spelling and language as quoted]; “Sandford in 1666 noted that the Lower Coast ‘abounds besides with Oyster banks and such heapes of shells as wch. noe time cann consume…’ Ferguson exaggerates still more: ‘...Cockles, Musses they have; and Banks, nay Mountains of Oysters (and some with Pearl) that seem to barocade the Cricks.’”

Gene Waddell, Indians of the SC Lowcountry

Photographs of a shell midden at Hobcaw Barony near DeBordieu Island , taken by SCETV in 2016.

, taken by SCETV in 2016.

Wendy Allen discusses marine research at Hobcaw Barony today.

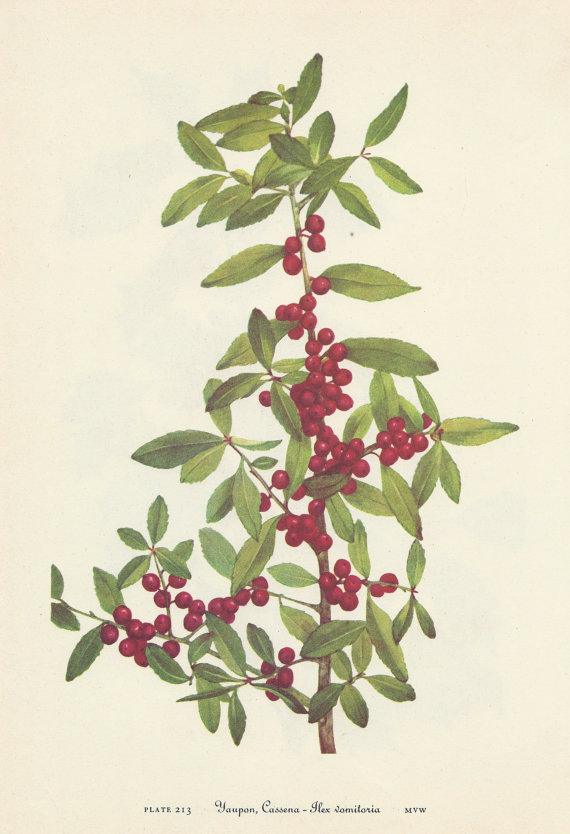

The black drink was a tea brewed predominantly by Southeastern Native Americans for a variety of social and ceremonial rituals. Consumption of the black drink was a defining cultural practice of the tribes once located along the coast from Virginia to Florida.

Often referred to as “cassina,”an Anglicized form of a Native American term, the tea is made by boiling parched yaupon holly leaves and twigs until they form a strong, dark-colored elixir.

The drink was mainly consumed by adult males of high social standing in order to attain ritual purity, but also served as a stimulating social beverage, as a medicine that improved physiological and psychological well-being, and to induce vomiting (likely for ceremonial purification).

John Lawson (1674-1711), an early English explorer and naturalist, discovered the origins of the black tea during his travels across the Carolinas in the 17th and 18th centuries. Lawson recounts,

“The Savages of Carolina have this Tea in Veneration above all the Plants they are acquainted withal, and tell you the Discovery thereof was by an infirm Indian, that labored under the Burden of many rugged Distempers, and could not be cured by all their Doctors; so one day he fell asleep and dreamed that if he took a Decoration of the Tree that grew at his Head, he would certainly be cured. Upon which he awoke, and saw the Yaupon or Cassena-Tree, which was not there when he fell asleep. He followed the Direction of his Dream and became perfectly well in a short time.”

A New Voyage to Carolina; Containing the Exact Description and Natural History of That Country: Together with the Present State Thereof. And a Journal of a Thousand Miles, Travel'd Thro' Several Nations of Indians. Giving a Particular Account of Their Customs, Manners, &c. (1709)

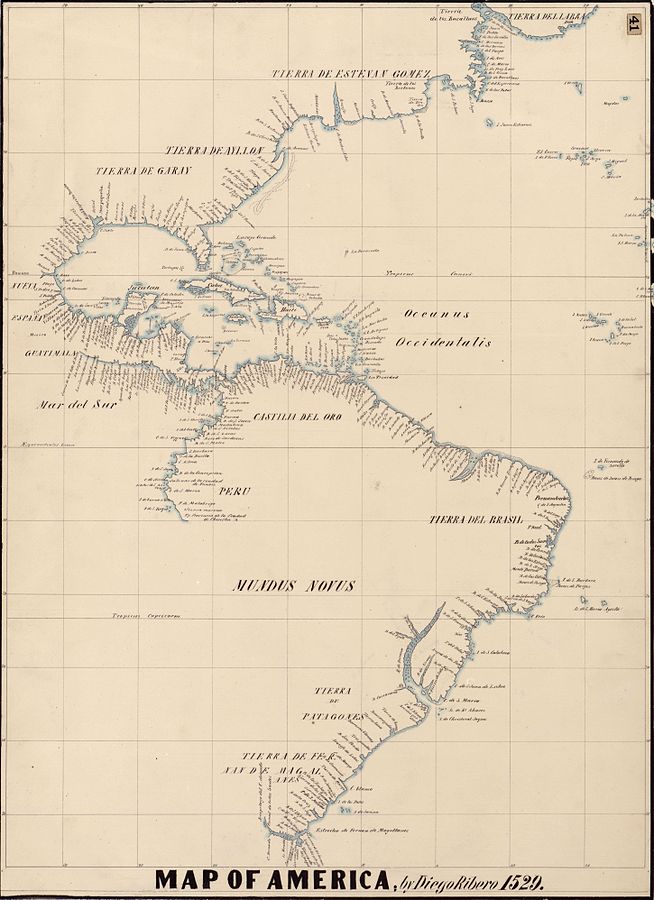

The Spanish were the first Europeans to reach the Carolina coast. In 1526, led by explorer and slaveowner Lucas Vasquez de Ayllon, six ships carrying 500 people from the island of Hispaniola landed near Cape Fear, North Carolina. They kidnapped 70 natives to sell in Hispaniola, one of whom they named Francisco de Chicora. Seeking to establish a colony, they moved south along the coast.

Somewhere near Hobcaw Barony, the lead ship, Capitana, struck a sandbar and sank, carrying with it most of the supplies. Traveling further south in the remaining ships, the colonists finally found the dry, high ground they had been seeking and established the settlement they called San Miguel de Guadalpe. Francisco de Chicora left the group and escaped into the woods.

Lack of supplies, disease and a slave insurrection doomed the colony. Ayllon and many others died and San Miguel de Guadalpe was abandoned after three months, the 150 survivors returning to the Caribbean. No material evidence of the colony has ever been found and its whereabouts are unknown.

This 1529 map by Diego Ribero depicts the southeastern coast of the North America as the "Tierra de Ayllon." Ribero served as the head cartographer for the court of Spain.