King’s Highway

Native American Hunting Practices

Native American Hunting Practices

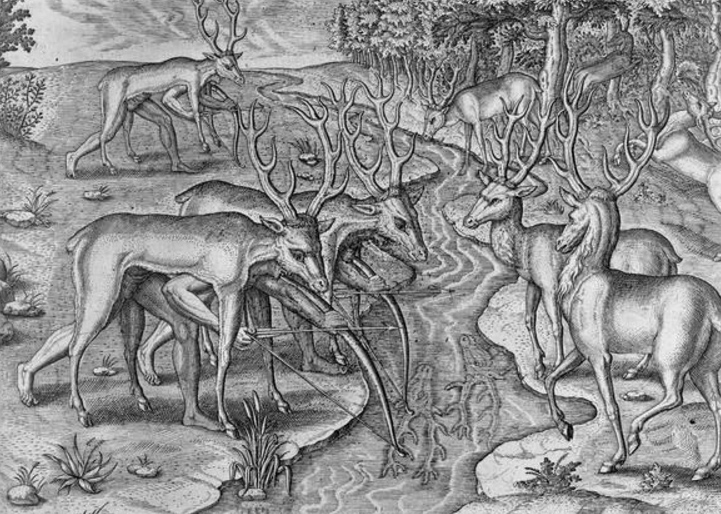

Hunting was a key element of food production among indigenous tribes in the coastal Southeast, alongside agriculture, gathering, and fishing. Native Americans on Hobcaw Barony would have hunted deer, hogs, turkeys, bobcats, panthers, black bears, rabbits and squirrels. One hunting method involved driving prey into an ambush by setting fire to leaves and underbrush using matches made of Spanish moss. John Lawson (1709) recounts this method of hunting; “Thus they go and fire the Woods for many Miles, and drive the Deer and other Game into small Necks of Land and Isthmuses where they kill and destroy what they please.”

Though this method of hunting may have seemed destructive to early European observers, it played an important role in the reproduction cycle within the forest’s ecosystem.The forests in which Native Americans once hunted were dominated by longleaf pines, a species of pine tree dependent upon fire to reproduce.

The bow and arrow is frequently referred to in historical accounts as the primary weapon used by Native Americans, although guns would become increasingly popular after trade increased between Europeans and Native Americans. According to John Lawson small game, including turkeys, ducks, and small vermin/ rodents were not worth the gunpowder and were hunted with the bow and arrow, which Thomas Ashe (1682) describes as being “...made of Read, pointed with sharp Stones, or Fish bones…”

Hobcaw Barony Forests

Hobcaw Barony Forests

In 1947 Belle Baruch hired Nolan Taylor, an experienced forester, as the plantation manager. Taylor convinced Belle Baruch of the importance of forestry management; in this 1957 photograph he oversees selective timber harvesting.

The forests of Hobcaw are a mix of hardwood and pine, including loblolly and longleaf varieties. Longleaf pine forests once dominated the eastern coastal plain of the U.S., stretching over 140,000 square miles, but they have been greatly reduced by centuries of logging and development. Nevertheless, they still play an important role in the region’s ecology, providing habitat for the endangered gopher tortoise and red-cockaded woodpecker.

The Belle W. Baruch Foundation works to maintain longleaf habitat through replanting and the use of prescribed burns. In this video the Foundation’s Executive Director George Chastain talks about the history of the Hobcaw forests.

Who Put the King in the "King's Highway"?

Who Put the King in the "King's Highway"?

In an article published in the May/June 2014 issue of South Carolina Wildlife Magazine, author Dennis Chastain clarifies the history of the name of this historic road.

Who Put the King in the "King's Highway"?

By Dennis Chastain

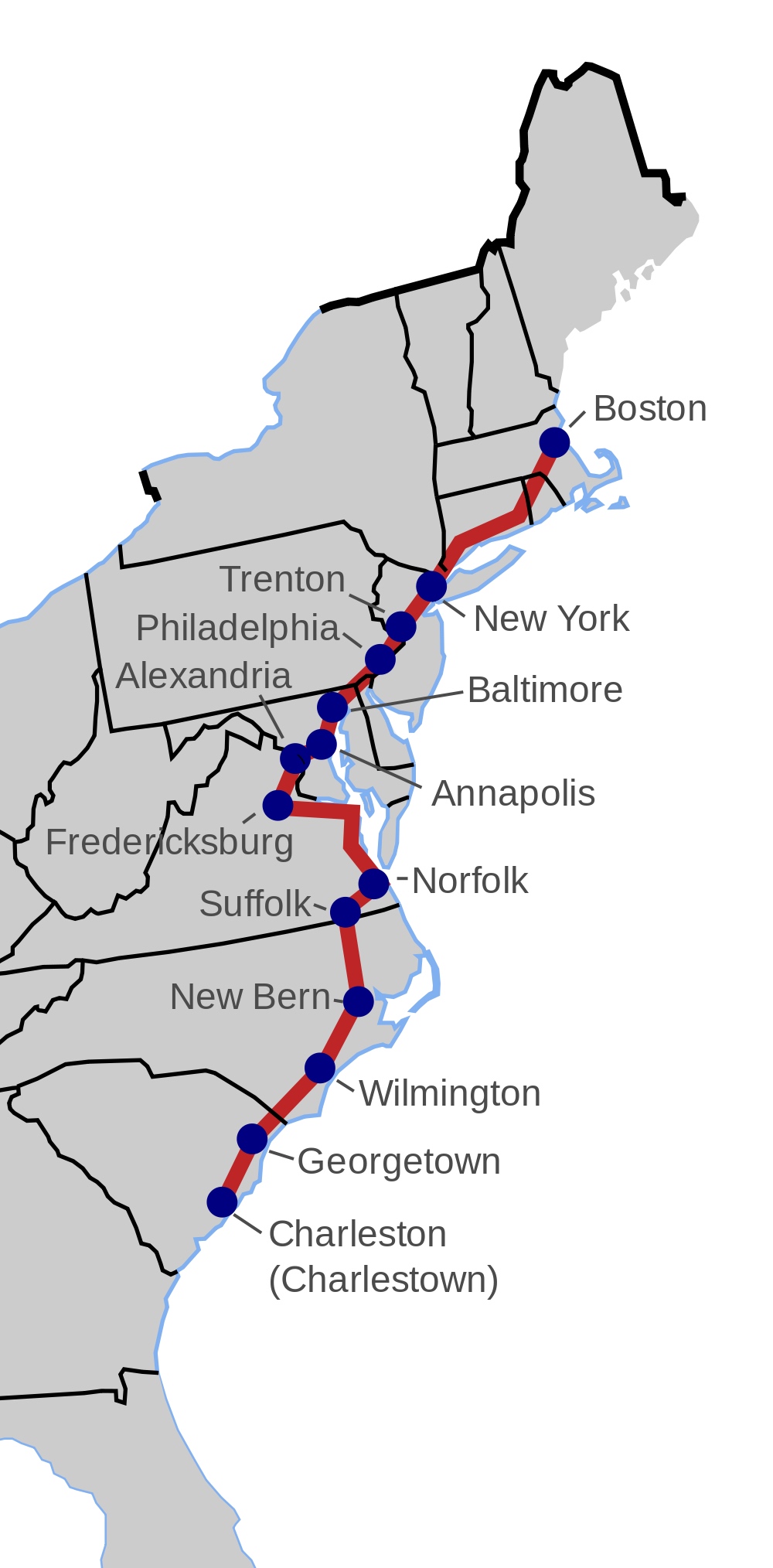

It is often stated that the origin of the 1,300-mile King's Highway from Boston to Charleston dates to an edict from King Charles II in 1650, which directed the colonies to build a post road connecting the thirteen colonies. Sounds pretty good, except for the fact that the South Carolina colony and Charles Towne did not even exist until 1670, when the original settlement occurred on the Ashley River. Not to mention the fact that until 1720, the colony took its orders and directives from the Lords Proprietors, not the King of England.

Here's what really happened:

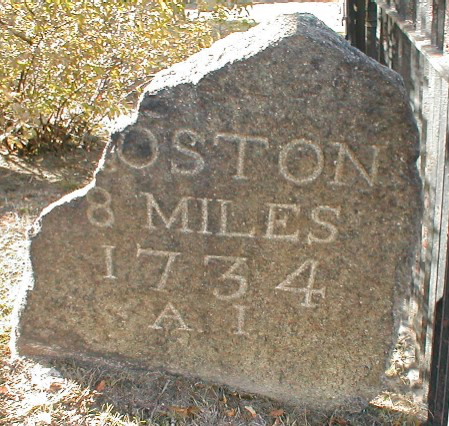

Yes, Charles II did direct that a post road be constructed in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and it proved very successful, both for getting the news from the remote corners of the colony to Boston and for getting from one place to another. The concept caught on in New England, and the thoroughfare took on the name the "King's Highway." The road was eventually extended and improved all the way to New York, and later, Virginia.

Meanwhile, as early as 1713, the colonial government in South Carolina began its own program of building roads and ferries, both along the coast and inland. Local committees were commissioned with the power to tax local landowners for the construction costs, and ferries over the Charleston harbor, North and South Santee rivers, and Winyah Bay were authorized with specific and very detailed charters issued for the ferry operators. By about 1735, it was possible, though certainly not easy, to travel from Charles Towne to the newly surveyed state line near Little River. This road came to be known as the "Georgetown Road."

Fast forward to 1938. During the Great Depression, the Works Progress Administration commissioned the Federal Writers program, which produced a very popular travelogue called Ocean Highway that covered a one-thousand-mile-long section of the continuous coast road from New Jersey to Florida. Since they knew from researching the road in the northern states that the road was called the King's Highway, they assumed that was also true in North and South Carolina – a false assumption.

In fact, the Georgetown Road had nothing to do with Charles II or the Boston Post Road. Nevertheless, the book repeatedly indicated that "the coast road follows the route of the old "King's Highway," and the name stuck. Years later, South Carolina's first official state historian, A.S. Salley, somewhat frustrated at the "myth" behind the then firmly-entrenched name, asserted that he had read numerous colonial era newspapers and reviewed countless old documents but had never come across a reference to the so-called "King's Highway."

Now we know why.

Reprinted with the permission of South Carolina Wildlife Magazine

The King's Highway on the Waccamaw Neck

The King's Highway on the Waccamaw Neck

The road called the King’s Highway traverses the length of the Waccamaw Neck. It goes through all four of the plantations that comprise Brookgreen Gardens - Laurel Hill, The Oaks, Springfield and Brookgreen - and it covers four miles on Hobcaw Barony, where it was a public road until 1930.

The King’s Highway leads through Hobcaw to Fraser’s Point, the end of the Waccamaw Neck, where Fraser’s Ferry once provided transportation across Winyah Bay to Georgetown. Although parts of the King’s Highway have been incorporated into U.S. 17, on Hobcaw Barony it still exists as a rutted sandy road, looking much as it would have centuries ago.

William Bartram, Naturalist

William Bartram, Naturalist

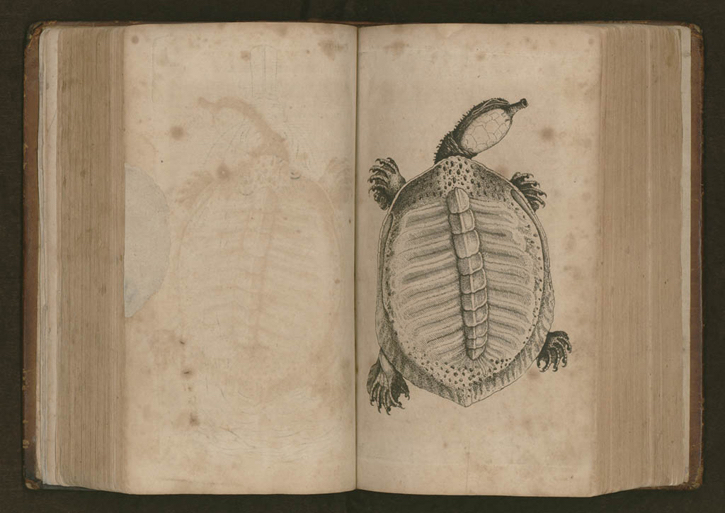

In 1773, the pioneering American naturalist William Bartram set off on a four-year excursion through eight southern colonies. In the course of his journey he discovered many new species of native flora and fauna, and spent time with Native Americans. He made careful notes on their lives and customs, believing he had much to learn from Indians’ relationship with nature. In addition to being a skilled writer, Bartram drew well, and included drawings of plants and animals in his book. Pictured here is a drawing of a soft shelled tortoise, which he describes as “very fat and delicious.”

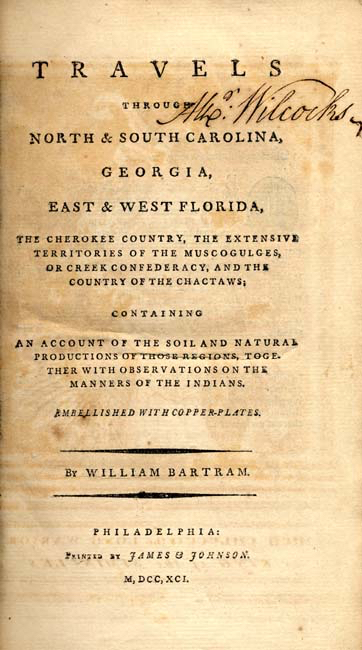

Bartram passed through the Hobcaw region in 1776, likely riding on the King’s Highway for at least part of that distance. In 1791 he published a book about his travels, the cover of which is pictured here.

In his book he included the following description of an encounter on Long Bay, known today as Myrtle Beach:

In three days more easy travelling, I crossed Winyaw bay, just below Georgetown, and in two days more, got to the West end of Long bay, where I lodged at a large Indigo plantation...It is pleasant riding on this clean hard sand, paved with shells of various colours.

Observed a number of persons coming up a head which I soon perceived to be a party of Negroes: I had every reason to dread the consequence; for this being a desolate place, and I was by this time several miles from any house or plantation, and had reason to apprehend this to be a predatory band of Negroes: people being frequently attacked, robbed, and sometimes murdered by them at this place; I was unarmed, alone, and my horse tired; thus situated every way in their power, I had no alternative but to be resigned and prepare to meet them, as soon as I saw them distinctly a mile or two off, I immediately alighted to rest, and give breath to my horse, intending to attempt my safety by slight, if upon near approach they should betray hostile designs.

Thus prepared, when we drew near to each other, I mounted and rode briskly up, and though armed with clubs, axes and hoes, they opened to right and left, and let me pass peaceably, their chief informed me whom they belonged to, and said they were going to man a new quarter at the West end of the bay, I however kept a sharp eye about me, apprehending that this might possibly have been an advanced division, and their intentions were to ambuscade and surround me, but they kept on quietly and I was no more alarmed by them. After noon, I crossed the swash at the east end of the bay, and in the evening got to good quarters. Next morning early I set off again, and soon crossed Little River at the boundary; which is on the line that separates North and South Carolina."

William Bartram, Travels through North and South Carolina, Georgia, East and West Florida, the Cherokee Country, etc, Ronald E. Latham, editor. Penguin, 1988.

The President’s Journey

The President’s Journey

During his first term as President, George Washington visited all 13 states. He made the journey to the South in the spring of 1791, leaving on March 21 and returning on June 4. Washington traveled south along the eastern seaboard, calling at coastal cities, and returned along a westerly route from Augusta, Georgia through the Piedmont of North Carolina to Virginia. A hero of the Revolution, he was highly regarded and welcomed with excitement and acclaim wherever he stopped.

He entered South Carolina near Little River and and rode along the beach of Long Bay, known today as Myrtle Beach. When he reached the Waccamaw Neck he was greeted by Dr. Henry Collins Flagg of Brookgreen Plantation, where he spent the night before proceeding to have breakfast at William Alston’s Clifton Plantation, part of present-day Hobcaw Barony. During much of this part of his journey he traveled on the King’s Highway, known in 1791 as the Georgetown Road. This painting depicts Washington as a young commander-in-chief of the Continental Army in 1776.

The G. Washington Poems

The G. Washington Poems

George Washington’s Diaries: April 1791

Saturday, 30th. Crossed the Waggamau to Georgetown by descending the River three miles. At this place we were recd. under a Salut of Cannon, and by a Company of Infantry handsomely uniformed. I dined with the Citizens in public; and in the afternoon was introduced to upwards of 50 ladies who had assembled at a Tea Party on the occasion.

P. B. Newman published The G. Washington Poems in 1986. Informed by Washington's diaries, they include two poems set in 1791 during Washington's Southern journey, as he visited Georgetown and points further south. The poet also shot footage of the King's Highway and the South Carolina coast, which illustrates the poems in the video below.

View Map

View Map