Enslaved people of the South Carolina Lowcountry used African, Native American and European plants and expertise to create their own distinct healing traditions.

The dandelion is an example of a plant brought to North America by Europeans, and used for medicinal purposes by Native Americans and enslaved Africans. A broth made from dandelions was taken to ease indigestion and other ailments.

Slaves brought knowledge of healing and root ways from Africa but often found their new setting supported different flora and fauna than their homeland. They also encountered a host of new diseases in their new world. Over time the slaves synthesized new methods (some learned from indigenous Americans, some improvised) with what they already knew. The end product was Gullah root medicine, which is reported to have been highly effective in relieving maladies common to the area.

Kincaid Mills, Genevieve C. Peterkin, Aaron McCollough, Editors. Coming Through: Voices of a South Carolina Gullah Community from WPA Oral Histories

Laura Carr was known as a “root doctor,” someone who understood how to use medicinal plants for healing and conjuring spells.

In 1999, the Belle W. Baruch Foundation refurbished the Laura Carr dwelling. When rotting interior boards were pulled away from the wall, workers found this small burlap bundle with human hairs protruding from the top.

Because Carr was the only known resident of the dwelling, and because of her reputation as a root doctor, it was assumed to be her “root pouch” or prayer sack.

The slave herbalist had another venue, one even less understood by whites: the realm of the spirit. Traditional African medicine taught that much sickness had its origins in spiritual evil, and drugs alone would not guarantee physical health. The spirit could have been sent by an enemy or could come of its own volition because of some lingering resentment when it had been a living being. In either case, the spirit had to be placated or exorcised.

Roger Pinckney, Blue Roots: African-American Folk Magic of the Gullah People

Although Laura Carr's spiritual beliefs had African origins, she was also a practicing Christian, and regularly attended Friendfield Church. This blend of religious belief and practice is a central feature of Afro-Christianity.

In this image from 1905, Laura Carr's house stands to the left and across the street from Friendfield Church.

An extensive record of the complex worldview of Gullah people on the Waccamaw Neck can be found in the oral histories collected during the 1930s for the Federal Writers Project.

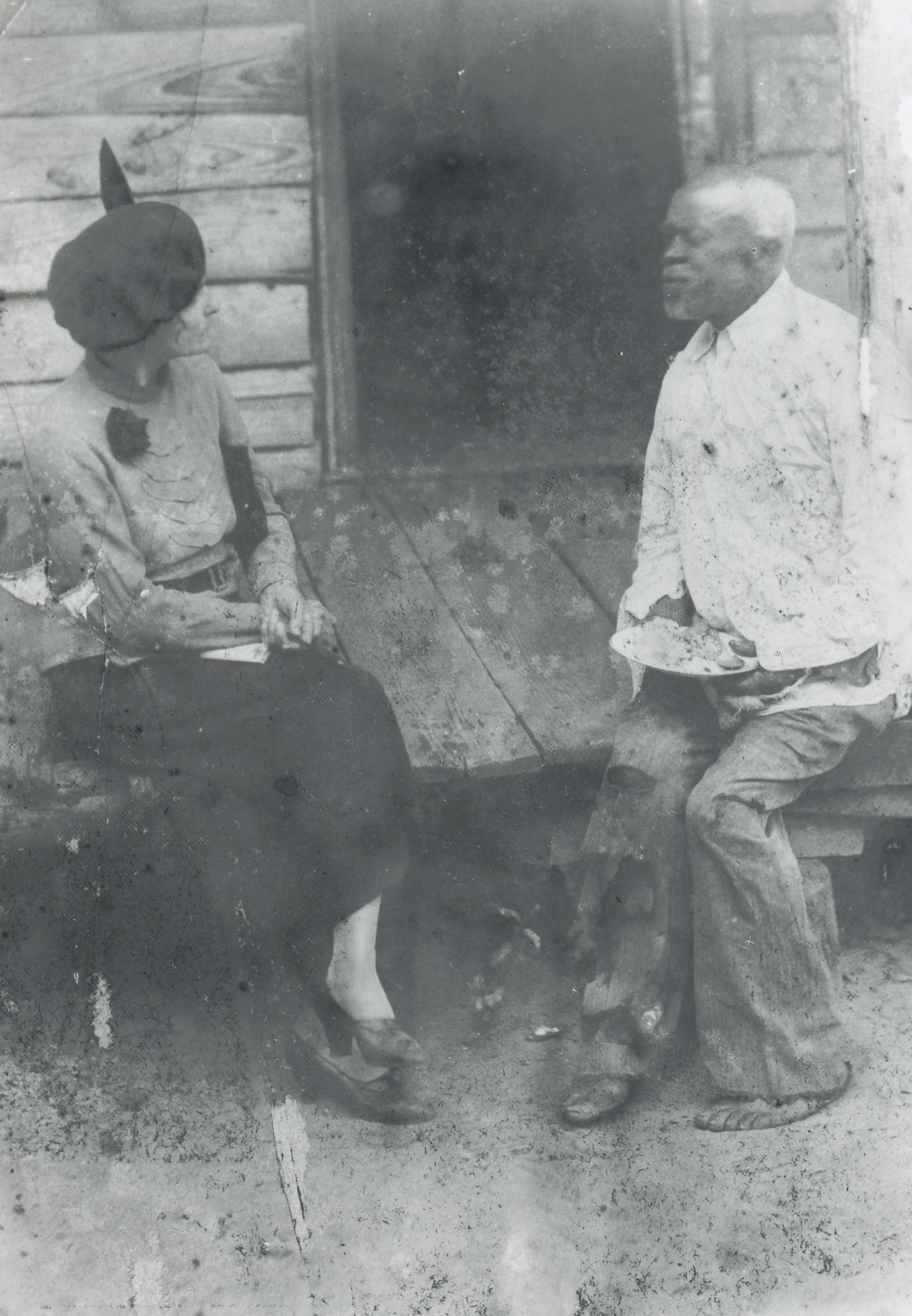

In this photograph, Genevieve Willcox Chandler interviews Ben Horry at his home in Murrells Inlet, a small Waccamaw Neck fishing village about 25 miles north of Hobcaw Barony.

Ben Horry, who was born into slavery in 1852, was eighty-seven when this photograph was taken. At one point he was involved in a property dispute with Joe Baruch, a cousin of Bernard, in which Joe Baruch shot and wounded Horry for trespassing.

Chandler worked as a folklorist for the Writers Project from 1936 - 1938, recording interviews with over 100 residents of All Saints Parish, many of them former slaves.

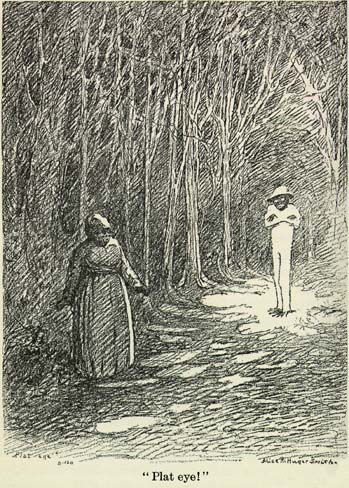

Addie Knox, another African American interviewed by Genevieve Chandler, told of an encounter with a plat-eye, a malevolent spirit with glowing eyes, said to harass travelers on lonely roads.

In an interview recorded on May 25, 1936, Knox explains that she is prepared for another such encounter through a combination of root medicine and trust in God. Chandler transcribed the interview to reflect the Gullah language.

Yas’m. I’m ready for ‘em. Gun-powder en sulphur. Dey is say Plat Eye can’t stan dem smell mix. No’um. Dey ain fer trubble me sense dat wan time. Uncle Murphy he witch docrer en he bin tell me how fer fend’em off. Dat man full ob knowledge. He mus hab gawd mind in’em. So I totes mah powder and sulphur en I carries stick in mah han en puts mah truss in Gawd.

The editors of a collection of Chandler’s interviews add this in a footnote to the story:

Religious views that are in some ways incompatible find a peaceable common ground in Gullah culture and in Addie Knox’s mind. ...The charmed powder and sulphur are a tangible nod to the West African animism that lived on as a vestigial feature of the Gullah worldview, providing protection from plat-eyes, hoodoo, conjure and the like. Her “truss in Gawd” is an obvious reference to the Christian faith that was also strong among the Gullah.

Kincaid Mills, Genevieve C. Peterkin, Aaron McCollough, Editors. Coming Through: Voices of a South Carolina Gullah Community from WPA Oral Histories

To return to the trail click NEXT STOP

To return to the Carr house click