Hobcaw Barony’s once plentiful pine forests and cypress wetlands provided much of the raw material for building vernacular structures, such as those in Friendfield Village. In the earliest part of the colonial period, old-growth pine forests stretched across the Southeast. “Heartwood,” the dense inner, non-living core of these trees, was preferred by builders for its strength and rot-resistance. The resilience of heartwood is seen the minimally preserved nineteenth century dwellings at Hobcaw Barony and in the weathered remains of barns, houses, and outbuildings across rural landscapes of the South.

Old-growth cypress trees, cleared to create rice fields, provided naturally pest-and-rot resistant wood ideal for weatherboard and shingles, work boats and submerged structures in canals and fields, such as sluice gates. The use of inferior, new-growth wood for repairs and additions of Friendfield Village structures in the twentieth century tells the story of massive deforestation of cypress and longleaf pine forests. Today examples of old-growth forests are few and exist mostly as protected sanctuaries and parks.

The buildings in Friendfield Village fall into a category known as “vernacular architecture,” a term describing places people experience as part of daily life, constructed without the involvement of a professional architect. The houses and church of Friendfield Village can serve as windows into the lives and culture of the people who lived here.

Taking into account the small size of the Friendfield Village dwellings and the big families who occupied them, one can assume a lot of village life took place on the street. These houses stand in sharp contrast to Hobcaw House, a large, imposing structure designed to accommodate relatively few people.

The American painter Edward Hopper, who visited the South Carolina Lowcountry in the 1920s, clearly had an appreciation for vernacular structures. The small dwelling in this 1927 painting by Hopper, entitled Cabin - Charleston, South Carolina, closely resembles Laura Carr’s house.

The builders of Hobcaw Barony’s colonial and antebellum structures used tabby primarily as as the cement for fired-clay chimney brick. Made of water, sand, ash and broken oyster shells, tabby may have originated on the North African coast, probably in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. It came to the New World with Spanish settlers in the sixteenth century and can be found in old and new buildings along the Southeastern coast.

While sand was readily available on the coast, builders at Hobcaw Barony might have not have acquired large quantities of oyster shells quite so easily. Perhaps they turned to the stockpiles of shells found in Hobcaw's salt marshes. These island-sized accumulations, or middens, are made up of oyster and clam shells and other materials discarded by Native American inhabitants, predating Europeans by thousands of years.

Today the deserted structures of Friendfield Village are surrounded by mowed green grass, with a quiet soundtrack of birds, insects, and the occasional tour group, but the Friendfield Village landscape was once very different. The stage for daily life was well-trod dirt weathered by nearly a century of activity. Washing, cooking, butchering, socializing and playing took place outside.

Wattle fences made of woven wood sticks, as seen in this 1905 photo, protected gardens from deer and wild hogs. Porches were social spaces, providing shade and protection from mud and pests, and bare earthen front yards served as outdoor rooms. Villagers swept yards clear of trash that might hide snakes or become cover for ticks. The tradition of the "swept yard" originated in Africa and was transferred to America during the plantation era, when it became common in both white and black households of every class.

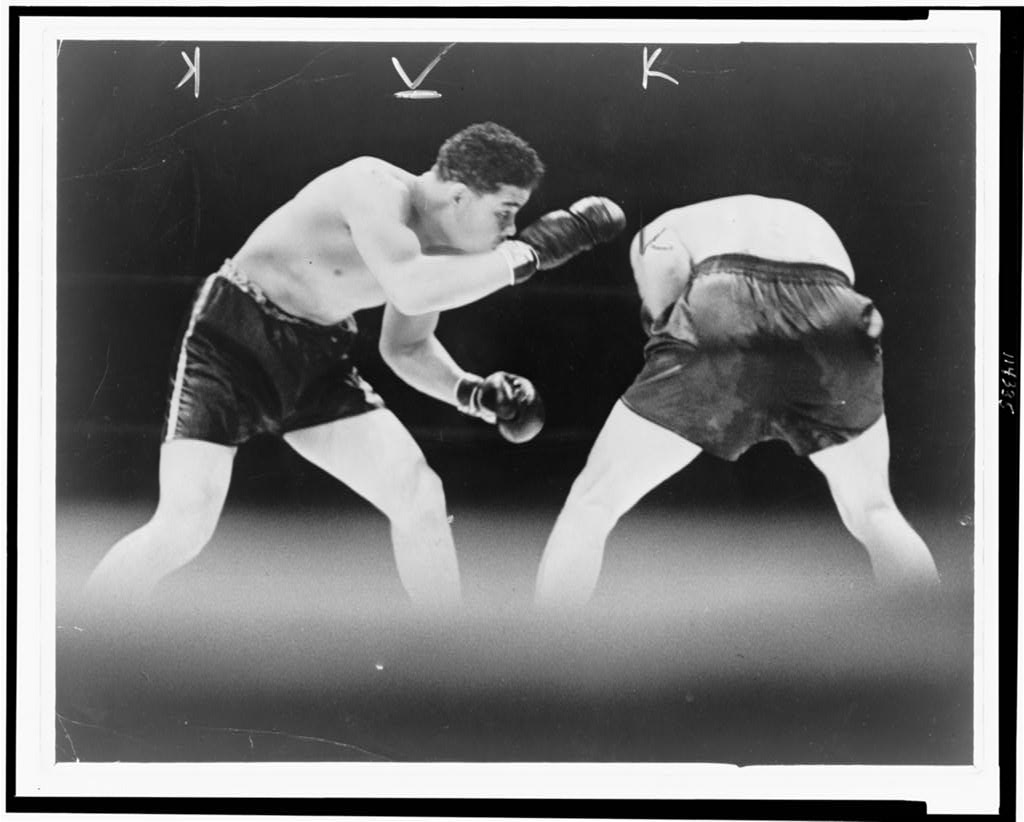

Although this dwelling is called the Logan house, we know very little about the Logan family. Without a living former resident to tell its story, this structure, like many vernacular buildings of its location and era, is largely a mystery. Former neighbor Joshua Shubrick shared a glimpse of its past on a tour of Friendfield Village in 2015 when he recalled a group of people listening to the boxing rematch between Joe Louis and Max Schmeling on the porch of this dwelling on June 22, 1938, gathering around a battery-operated radio.

Millions of people all over the world listened to the fight, which was broadcast in four languages. The Brown Bomber, who lost his first fight with Schmeling in 1936, beat the German fighter in two minutes and four seconds. The fight was the pinnacle of Louis' career and one of the great sporting events of the twentieth century.