Bernard Baruch purchased Hobcaw Barony between 1905 and 1907, during the Jim Crow era, the period after the collapse of Reconstruction, when laws enforced racial segregation and codes of racial etiquette affected every aspect of daily life for African Americans.

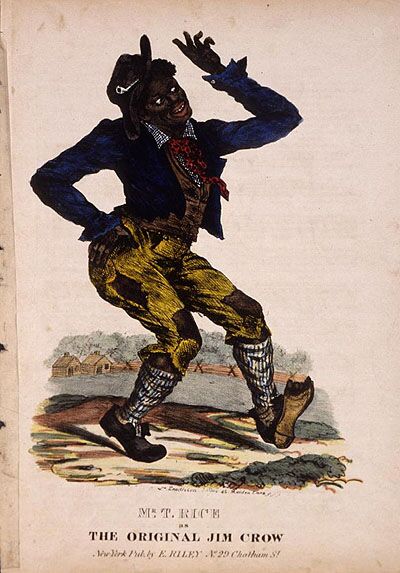

The term “Jim Crow” is thought to have originated in the 1830s with a caricature of blacks performed in blackface by a white comic named Thomas Dartmouth Rice. Rice sometimes sang a song entitled “Jump Jim Crow.” The image depicted here is the cover of the sheet music for that song.

The Smithsonian National Museum of American History lists a sample of Jim Crow laws on their website, Separate Is Not Equal:

“All railroads carrying passengers in the state (other than street railroads) shall provide equal but separate accommodations for the white and colored races, by providing two or more passenger cars for each passenger train, or by dividing the cars by a partition, so as to secure separate accommodations.” - Tennessee, 1891

“Marriages are void when one party is a white person and the other is possessed of one-eighth or more negro, Japanese, or Chinese blood.” - Nebraska, 1911

“Separate free schools shall be established for the education of children of African descent; and it shall be unlawful for any colored child to attend any white school, or any white child to attend a colored school.” - Missouri, 1929

“It shall be unlawful for a negro and white person to play together or in company with each other in any game of cards or dice, dominoes or checkers.” - Birmingham, Alabama, 1930

The world of Jim Crow was humiliating and dangerous for African Americans. Blacks who lived on Hobcaw Barony and other Lowcountry lands that were bought by wealthy Northerners faced the additional problem of being at the mercy of one affluent, powerful individual or family, like the Baruchs.

By the standards of the day, Baruch did not treat Hobcaw’s African-American residents badly.

He hired them, albeit at a low wage, to help manage the property, serve as hunting guides, and grow and cook food for his family and guests; he paid for their health care and education, and he doubled the size of many of their houses.

Baruch thought of himself as benevolent:

One reason I established a second home in the South was that my mother had asked me not to lose touch with the land of my forebears. She also had urged me to try to contribute to its regeneration and, in particular, to ‘do something for the Negro.’ Her urging never left my mind, and in all my activities in the South I have always sought to better conditions there and somehow to help improve the Negro’s lot.

Bernard M. Baruch, Baruch: My Own Story

During the 1920s and ‘30s black music was becoming increasingly popular among whites, and in New York City they flocked to see black performers in Harlem at places like the Cotton Club. For Baruch and his guests, the church services and dance performances at Hobcaw had the same sort of exotic flavor.

On Saturday nights dances were held in the barn. We gave prizes to the best dressed among the men and women, boys and girls. Practically all the modern dances later popularized in New York, Paris and London I first saw at Hobcaw. The “music” at these dances was furnished in part by a mouth organ, but mostly by clapping hands and patting feet which provided a rhythm which, I have been told, was much like that created by the native drummers in Africa.

Bernard Baruch, Baruch: My Own Story

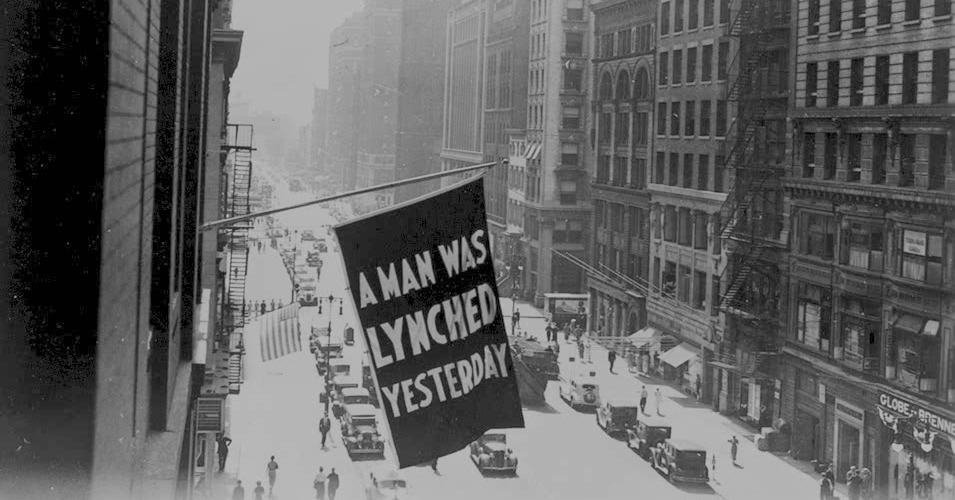

For blacks at Hobcaw Barony during Jim Crow, the indignity of providing entertainment for white observers was minor, compared to other life-threatening situations confronting them, such as lynching.

These racial murders occurred across the South at the rate of two or three a week in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

In his memoir Bernard Baruch recalls an attempted lynching at Hobcaw, in front of his family home. A young white woman whom Baruch had hired to teach the children of his white workers reported being attacked by an African American man:

After a search of a few hours the fugitive was caught and brought to the yard of our house. There, surrounded by a sizable crowd, were the sheriff, my superintendent, Harry Donaldson, and Captain Jim Powell. The crowd was for stringing up the culprit then and there. Someone tossed a rope over a limb of one of the moss-hung oaks that shade the front lawn.

Jim Powell, seeking some way of preventing a lynching, strode into the excited throng and asked to be heard.

“Don’t lynch him here in the yard,” he pleaded. “Miss Annie” - referring to my wife - “and Miss Belle and Miss Renee” - meaning my daughters - “would never come back to Hobcaw again. It would spoil the place for them forever. Let’s take him up the Neck.”

Bernard Baruch, Baruch: My Own Story

Baruch goes on to explain that the sheriff rescued the alleged attacker from the mob and took him to Georgetown where he was “tried before a jury, convicted and hanged.” Baruch decries lynching as having left a stain upon the South.

To return to the trail click NEXT STOP

To return to the Hobcaw House Front Lawn click