The menu at Hobcaw House, in the tradition of Southern plantations, was shaped by West African, Native American and European foodways.

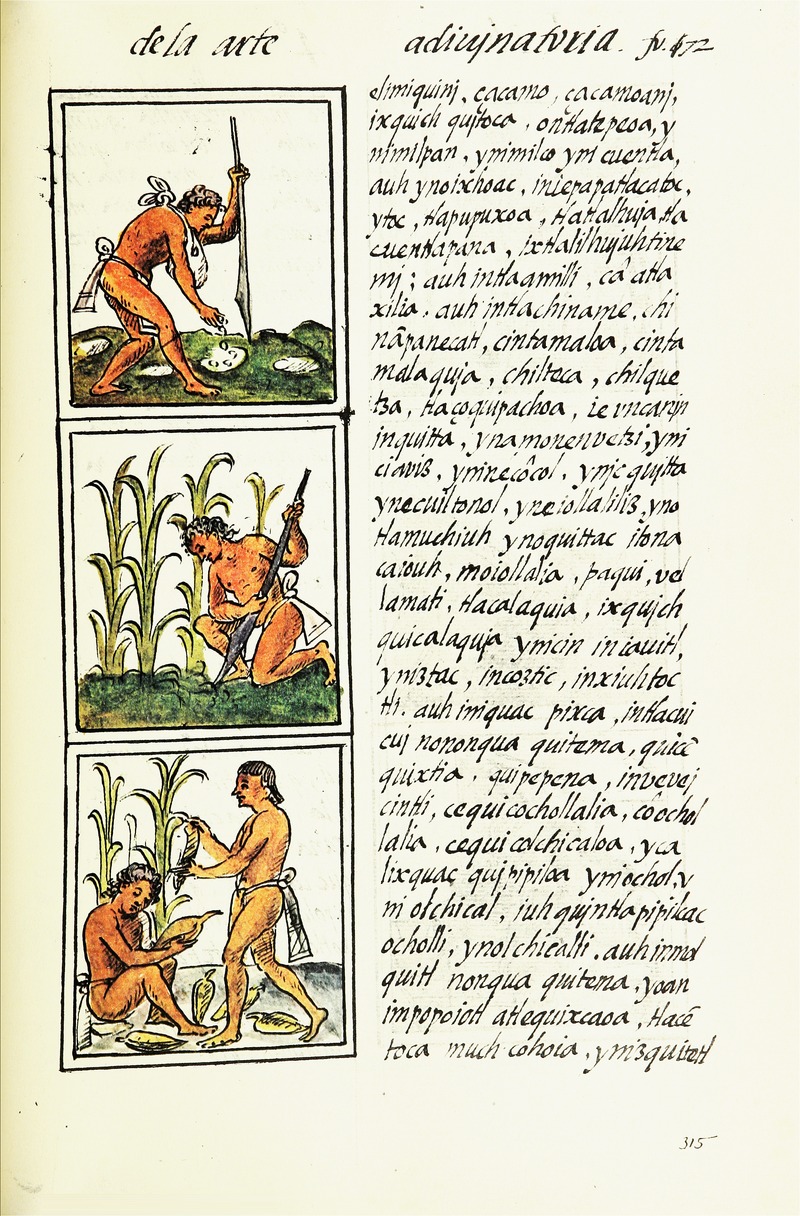

Before Columbus's arrival in the Caribbean in 1492, the Americas were a separate biological world from Europe and Africa. In this image, Aztec farmers in Mexico plant maize, a food unknown in Europe.

With European contact began an interchange of plants, animals, and bacteria between these worlds, known today as the Columbian Exchange.

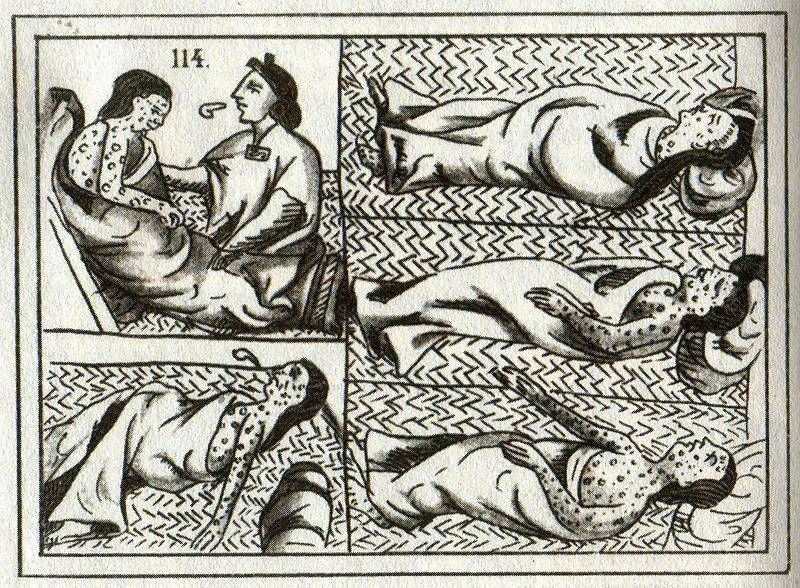

While this exchange had enormous benefit for Europeans and their colonies, it introduced diseases to which Native Americans had no resistance, such as smallpox. These diseases eventually killed as much as 90 percent of the native population. The print below by Spanish missionary priest Bernardino de Sahagún, illustrates the devastating effects of smallpox on an Aztec victim.

Maize, or corn, was one of the most important and beneficial foods the Europeans encountered in the Americas. It had been cultivated in the New World for thousands of years.

Corn was quickly introduced into Africa in the context of the slave trade, so that by the time enslaved Africans arrived in South Carolina they would have been familiar with it.

Another important food plant that made its way from the Americas to Africa was the peanut. Both corn and peanuts play a central role in modern Southern foodways.

South Carolina’s culinary traditions, developed over nearly 400 years of trade between Europe, West and Central Africa and the Americas, reflect the blending of cultures that made up the Atlantic World. Out of this exchange grew a creolized cuisine with distinctive African and American influences.

Although we do not know a great deal about the meals that were eaten at Hobcaw House, we can assume that they incorporated traditional African-American foods and cooking techniques, since at least three of the cooks - Charlie McCants, Sr., Maudess McClary and Daisy Kennedy - were members of Hobcaw’s African-American community.

The diamondback terrapin, a turtle once common to the rice fields and marsh creeks of South Carolina, was coveted by Southerners for its delicious meat.

The Baruchs kept terrapins in a pen at Hobcaw Barony and Bernard Baruch once sent a box of them to his friend Georges Clemenceau, who was the Prime Minister of France during WWl. When Baruch asked Clemenceau whether he had enjoyed them, the Frenchman replied that he had found them “too amusing” to eat.

Turtle was considered a delicacy in Afro-Caribbean cultures as well. The Gullah term for turtle is “cooter,” thought to derive from the Malinke word “kuta.”

Whether eaten as turtle soup or cooter stew, turtle was a dish enjoyed by the African-American residents of Hobcaw as well as by the Baruch family and their guests.

To return to the trail click NEXT STOP

To return to the Hobcaw House Kitchen click