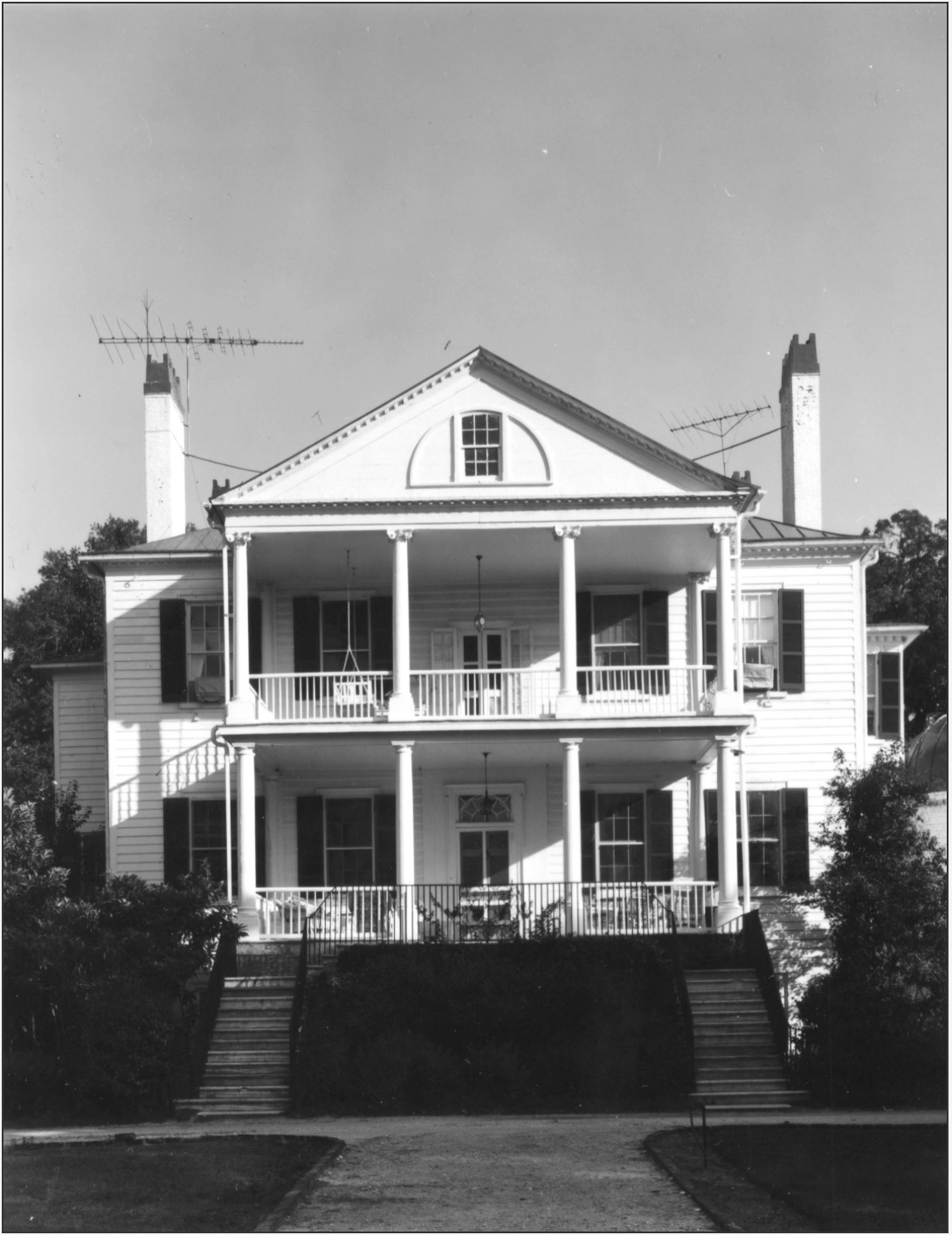

Hopsewee Plantation, located along the North Fork of the Santee River about 13 miles south of Georgetown, is the birthplace and childhood home of Thomas Lynch, Jr., a signer of the Declaration of Independence for South Carolina. Lynch’s father, Thomas Lynch, Sr., was a wealthy rice planter, and the house he built between 1735 and 1740 still stands.

Both Thomas Lynch, Sr. and his son were involved in Colonial and Revolutionary era politics. Lynch, Sr. attended the Continental Congress in Philadelphia in 1774, and father and son represented different districts in the First Provincial Congress of South Carolina early in 1775. Later that year, while in attendance at the Second Continental Congress, Lynch Sr. suffered a stroke, leaving him near death.

His son, who was recovering from a debilitating illness himself, was appointed to succeed him. Lynch, Jr. traveled to Philadelphia to care for his father, and while there signed the Declaration of Independence. Lynch, Sr. died in Annapolis en route back to South Carolina. In 1779, hoping to recover his health, Thomas Lynch, Jr., age 30, and his wife Elizabeth sailed for France, but the ship was lost, and the young couple perished at sea. Though Thomas Lynch, Jr. was not the first of the signers of the Declaration of Independence to die, he was the youngest at the time of his death.

Thomas Lynch sold Hopsewee Plantation to Robert Hume in 1762. In 1844 Hume’s heirs put the estate up for sale and his great-grandson John Hume Lucas bought the plantation, continuing to grow rice there. After the Civil War, rice was never grown on Hopsewee again.

The Lucas family sold Hopsewee in 1914, and it passed through several hands until it was purchased by Mr. and Mrs. James T. Maynard in 1969. They renovated the plantation house and opened it to the public in 1970 for scheduled tours, events and sweetgrass basket-making workshops. They also operate a tea room on the property.

Chicora Wood, located twelve miles northeast of Georgetown on the Pee Dee River at Plantersville, is best known as the home of the prosperous rice planter Robert F. W. Allston, a governor of South Carolina and a leading advocate of secession. Allston owned a number of plantations, including parts of Hobcaw Barony; in 1860 his enslaved labor force numbered 630 and his network of plantations produced 1,500,000 pounds of rice.

Educated at West Point, Allston served in the South Carolina state legislature for 24 years and was governor from 1856 to 1858. He and fellow Waccamaw Neck rice planters John I. Middleton, and Plowden C.J. Weston, were among the state's leading radical secessionists. The six Georgetown District delegates to the Secession Convention in December, 1860, all rice planters, voted unanimously for secession.

Benjamin Allston, Jr., Robert’s father, purchased the lands that would make up Chicora Wood in 1806 from Alexander Rose, a Charleston merchant. Robert Allston and his brother William inherited the property upon their father’s death in 1819, and Robert eventually bought out his brother, becoming full owner of the plantation in 1832. At this point it was called Matanzas, named after a location in Cuba from which the plantation slaves were believed to have been brought. The name was changed to Chicora Wood in 1853.

Robert Francis Withers Allston was a successful and scientific rice planter, often writing articles for De Bow’s Review, a popular magazine on commercial agriculture that championed slavery and was widely circulated throughout the South during the mid-nineteenth century. In 1855, a sample of rice grown at Chicora Wood won a silver medal at the Paris Exposition.

Robert F. W. Allston died in 1864, during the Civil War, and at the end of the war his heirs were forced to sell all of their properties in order to cover heavy debts against their estate. Only Chicora Wood, which had been awarded to Allston’s wife, Adele Petigru Allston, as her dowry, was saved. Mrs. Allston lived and planted rice at Chicora Wood until her death in 1896.

At that point her daughter, Elizabeth Waties Allston Pringle, who already owned nearby White House Plantation, purchased Chicora Wood. Elizabeth planted rice at both of her plantations and wrote articles on her experiences for The New York Sun between 1904 and 1907. The articles were later collected and published in the book, A Woman Rice Planter, in 1913.

Arcadia Plantation dates from the eighteenth century, when it was known as Prospect Hill. It was a large, productive rice plantation, one of many on the Waccamaw, Santee and Pee Dee Rivers that together made up the Lowcountry Rice Kingdom. In addition to creating great wealth, Arcadia was owned by three powerful South Carolina families: the Allstons, Hugers, and Wards, all of whom were active in the political and social affairs of the state .

Prospect Hill was a royal grant made to the brothers Anthony and George Pawley between 1732 and 1737. Joseph Allston acquired the property in 1769; he owned several plantations in the area, including one north of Prospect Hill used by Francis Marion in 1781 to store rice. At Joseph’s death, his son, Thomas, inherited Prospect Hill and built the current house, which was completed around 1794.

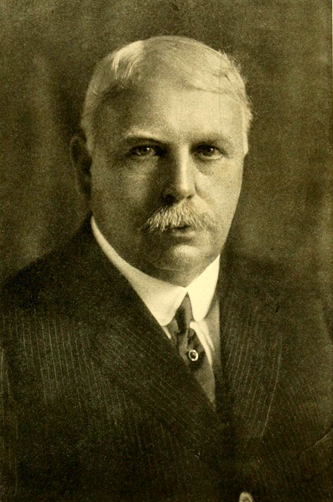

After Thomas’s death, his widow, Mary Allston, married Benjamin Huger, a member of the South Carolina Legislature and the U. S. Congress. She outlived her second husband and by 1838 she had sold Prospect Hill to Joshua John Ward for $130,000. Ward’s heir, Benjamin Huger Ward, sold it in 1906 to Dr. Isaac Emerson, a millionaire from Baltimore who had made his fortune by inventing a digestive remedy known as Bromo-Seltzer.

Dr. Emerson purchased six additional former rice plantations on the Waccamaw River over the next few years: Forlorn Hope, Clifton, Rose Hill, Bannockburn, Oak Hill, and Fairfield. Between 1906 and 1925 he pieced together the seven plantations to create a personal hunting retreat that he called Arcadia. The Emersons expanded the plantation house at Prospect Hill and made it the main residence.

Dr. Emerson’s daughter, Margaret, married into another powerful, affluent family - the Vanderbilts. Her husband, George Vanderbilt, was the son of Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt Sr., who died in 1915 in the sinking of the Lusitania. Alfred was the great-grandson of railroad and shipping tycoon Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt, one of the wealthiest Americans in history. In 1931, Emerson left Arcadia to George and Margaret, who used Arcadia as a hunting preserve and hosted large shooting parties.

The Vanderbilts willed the entire plantation to their only daughter, Lucille Vanderbilt Pate, who resides at Arcadia today, where she has preserved 8,000 acres of land along the Waccamaw and occasionally opens the property to the public for tours. The remainder of the Arcadia property, between Highway 17 and the ocean, is now the development known as the DeBordieu Colony.

Beneventum Plantation, loosely translated to mean “good wind” or “welcome” in Italian, is located near the Black River off Highway 701. One of the earliest successful rice plantations in the Georgetown area, it is significant because of its association with Christopher Gadsden.

Gadsden was the principal leader of the South Carolina Patriot movement in the American Revolution, a delegate to the Continental Congress and a brigadier general in the Continental Army during the War of Independence. One of the earliest opponents of Great Britain in South Carolina, Gadsden was the originator of the “Don’t Tread on Me” flag. His plain but vigorous language gave him a reputation as a firebrand.

After Gadsden’s death in 1805, the executors of his estate sold Beneventum to John Julius Pringle, Attorney General of South Carolina from 1792 to 1808 and member of the South Carolina House of Representatives. Pringle died in 1843, leaving Beneventum to his son, Robert. In 1850 Beneventum produced 420,000 pounds of rice with the labor of 142 enslaved people.

Robert Pringle died in 1863 and Beneventum was sold to George A. Trenholm, the treasurer of the Confederate government, on whose life it is said Margaret Mitchell based the character Rhett Butler of Gone with the Wind. Beneventum Plantation has since changed hands many times and today remains privately owned.

Mansfield Plantation can be traced back to 1718, when John Green acquired a grant for 500 acres in Craven county (as the Georgetown region was once called) along the Black River. After Green’s death in 1750, the land was sold to James Coachman. In 1754, Susannah LaRoche Man, the widow of Dr. James Man, purchased the land, and named it Mansfield in honor of her late husband. She received a grant in 1770 for an additional 400 acres of land between the Black and Pee Dee Rivers, which were added to Mansfield.

The plantation was most productive in 1840 under the ownership of Mary Taylor Lance (Susannah Man’s granddaughter) and her husband, Dr. Francis Simmons Parker. Parker had studied at the College of Charleston and Charleston Medical College, but gave up medicine because rice planting proved to be so lucrative. Parker experimented with different fertilizers in the soil at Mansfield in an effort to maximize production, and found that bat dung produced the highest yields of rice. He shared results and swapped advice with fellow members of the Planters Club on the Pee Dee and the Winyah and All Saints Agricultural Society. In 1850, Mansfield Plantation produced 375,000 pounds of rice; ten years later that amount had jumped to a staggering 1,440,000 pounds.

After emancipation of the slaves and the Civil War, the Georgetown County rice planters struggled to make their plantations profitable again, but producing rice without slave labor was difficult. A series of disastrous hurricanes, and the competing rice industry that had developed in Louisiana and Arkansas, spelled the death of the Rice Kingdom. By 1912, Mansfield was no longer producing rice, and was sold to Charles W. Tuttle, a native of Auburn, New York, who made the property his winter home and hunting club.

Mansfield Plantation changed hands several more times throughout the twentieth century. In 2004 it once again became the property of the Parker family, when John Rutledge Parker, great-great grandson of Dr. Francis Parker, purchased the property with his wife, Sally Middleton Parker.

Hampton Plantation is located on Wambaw Creek in northern Charleston County, near the Santee River. Although it is south of Georgetown, Hampton Plantation is part of the Lowcountry Rice Kingdom. On the Santee, as on the Waccamaw, the Black and the Pee Dee Rivers, planters converted freshwater swamps into highly productive rice fields using enslaved laborers. Hampton Plantation is especially notable for its association with several prominent figures from America’s early history.

Eliza Lucas Pinckney - She was the mother of Harriot Pinckney who, with her husband, Daniel Huger Horry, made her home at Hampton Plantation in 1768. Eliza Pinckney (1722–1793) was a business pioneer who is credited with launching the indigo industry in colonial South Carolina. Based upon experiments she conducted, the crop became viable for cultivation in South Carolina, and grew into a staple of the state’s economy. Between 1746 and 1748 the volume of indigo exported from Charleston grew from 5,000 pounds to 130,000 pounds, rivaling rice as cash crop. In her later years Pinckney lived with her daughter at Hampton. One of Eliza Lucas Pinckney’s sons, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, was a signer of the U.S. Constitution, and the Federalist presidential candidate in 1804 and 1808; Her other son, Thomas, was a governor of South Carolina and ambassador to Great Britain.

George Washington - The President stopped at Hampton Plantation in 1791 while visiting South Carolina on his southern tour. While at Hampton he was asked whether he thought a live oak tree growing in front of the house should be cut down. He replied that it should not, and the tree still stands today, known as the Washington Oak. President Washington was a great admirer of Eliza Lucas Pinckney and served as a pallbearer at her funeral.

Archibald Rutledge - Eliza Lucas Pinckney’s granddaughter, Harriot Pinckney Horry, married Frederick Rutledge in 1797. They made Hampton Plantation their home, and it continued to be owned by the Rutledge family for nearly two centuries. Archibald Rutledge, born in 1883, grew up there. Named South Carolina’s first Poet Laureate in 1934, he lived in Pennsylvania for many years, returning home to live at Hampton in 1937 and writing a book about the plantation entitled Home By the River. He published widely, his articles and poems appearing in Outdoor Life, Field and Stream, and dozens of other magazines, and he wrote more than 50 books. In 1971 Archibald Rutledge and his family gave Hampton Plantation - the house and 322 acres of land - to the South Carolina State Park Service. It is a State Historic Site and is open to the public.

Richmond Hill Plantation lands were situated northwest of Highway 17 near Murrells Inlet, extending from the Waccamaw River to the ocean. The archaeologist James Michie conducted a study of Richmond Hill during in the 1980s, revealing evidence of Native American habitation, including ceremonial burial mounds, and a Revolutionary War earthen fort. Michie’s investigations also identified remains of the planter’s house, two possible overseers’ houses, approximately 20 slave houses, a slave cemetery, a rice barn, and rice fields and dikes.

Richmond Hill’s European history began in 1711 when a 48,000 acre tract along the Waccamaw river was split three ways by John Murrell. Eventually, two southern sections of this land were combined to make Richmond Hill plantation. Murrell’s two daughters, Elizabeth and Ann, inherited the two southern tracts of land. In 1791, Anne Vaux, granddaughter to Anne Murrell Pawley, became the sole owner of her family’s tracts.

John D. Magill acquired Richmond Hill in 1825. By then it was producing rice along with subsistence crops (corn, oats, and sweet potatoes), and records show that Magill paid taxes for 892 slaves. It is said that Magill treated his slaves horrifically and punished them using brutal techniques, such as hanging, shooting, and even drawing and quartering. It can be verified that many of his slaves tried to escape, as he placed more advertisements for runaway slaves than any other planter. Not surprisingly, his plantation produced below-average yields of rice compared with others along the Waccamaw.

John Magill died in 1864, leaving Richmond Hill to his son, John, who filed for bankruptcy and sold the plantation five years later. The property fell into disrepair and by 1930 the plantation house, the overseers’ houses and the slave dwellings had all burned.

William Kimbel, owner of neighboring Wachesaw plantation, purchased Richmond Hill in 1930 to develop as a personal hunting estate. He let Richmond Hill be reclaimed by nature, until its past was rediscovered by James Michie in the 1980s. Now the Wachesaw-Richmond Hill tract is a retirement community, like many other plantations along the Waccamaw Neck, but its archaeological record has been restored.

In 1850, 1,092 slaves produced 4,000,000 pounds of rice on Joshua John Ward's six plantations, including Alderley. At that time, people of African descent greatly outnumbered whites on the Waccamaw Neck, and it can be assumed that there are many burial grounds on Hobcaw Barony that serve as their resting places.

One of the known burial sites is Alderley Cemetery, located in a heavily wooded area in the northeast section of Hobcaw. Thirty-nine gravesites have been identified at the cemetery and it is likely many more remain. Reverend Abraham Wright is buried here. He was a pastor at Friendfield Church, and his wife taught at Strawberry School.

As in Marietta Cemetery, some of the graves at Alderley Cemetery are decorated with bleached shells, glass and other objects, reflecting Afro-Christian burial practices and the beliefs of the individuals who once lived and worked on the plantation. These cemeteries provide a valuable resource for the study of the culture and history of enslaved Africans and their descendants.

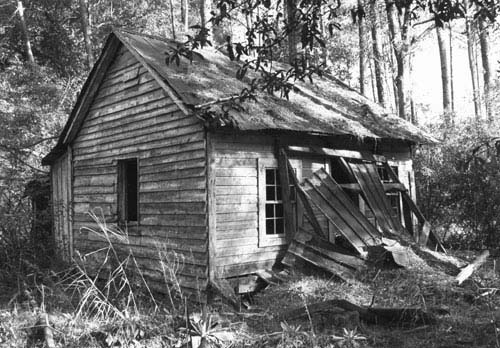

From south to north, eleven named rice plantations make up today’s Hobcaw Barony. They are Calais, Michau, Cogdell, Strawberry Hill, Friendfield, Marietta, Bellefield, Youngville, Oryzantia, Crab Hall and Alderley. The slave dwelling pictured here is the last remaining building on the grounds of the former Alderley Plantation. This photograph was taken in 1994, before the building was restored to its present condition.

Alderley Plantation was originally developed in 1766 by Scotsman Robert Heriot. He died in 1792, and the plantation was sold to Benjamin Huger, Jr., who later gave it to his brother, Francis Kinloch Huger. Huger married Harriott Lucas Pinckney, the granddaughter of Eliza Lucas Pinckney, the woman who introduced indigo to South Carolina.

A native of Antigua, Eliza Lucas Pickney, developed a strain of indigo suited to South Carolina's soil and climate. Her work, which depended in part upon the experience and expertise of enslaved people from Africa and the West Indies, had a major impact on the agriculture and economy of the state during the colonial era.

In 1848 Huger sold Alderley to Joshua John Ward. It remained the property of the Ward family until it was acquired by Bernard Baruch as part of Hobcaw Barony in 1907.

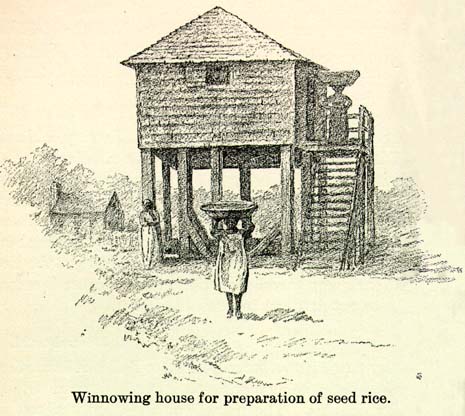

There are numerous steps in preparing rice for human consumption, the last of which is milling, in which the inedible husk of the rice is removed. Before the development of automated rice mills in the late eighteenth century, rice processing depended upon the labor of enslaved Africans, who milled the rice by hand using a mortar and pestle. Using this method, only a small amount of rice could be processed at a time. Trying to mill too much rice at once resulted in broken grains that were worth less money.

The mortar and pestle technique originated in West Africa. In this clip from SCETV's Family Across the Sea (1999), residents of a village in Sierra Leone mill rice using the mortar and pestle method. The sides of the pestle (the pole) move the rice around the mortar (the bowl), gently cracking and loosening the tough outer hull of the rice and separating it from the softer, edible center.